A select XI cricket blog posts of 2020

How did 2020 affect cricket blogging? Despite there being a lot less cricket played and very much less spectated than most would have planned, we blogged on. For a couple of months in the early summer, our method appeared to have infiltrated the professional media, which switched from match previews and reports to traditional blogging fare: nostalgia, lists and ‘things I would change about cricket’ pieces.

It filled their column inches, but their efforts didn’t really come up to scratch, particularly when compared to the quality output highlighted here. What follows is my personal selection of eleven blog posts from the year. None, to the best of my knowledge, was written for money and none of the writers has been featured in my nine previous annual selections.

It turned out that cricket in the UK found a sweet-spot in 2020, between the first wave of the pandemic and the autumn resurgence. In the early summer, however, it had seemed that the recreational game would be prohibited. The writer and club cricketer, Roger Morgan-Grenville (@RogerMGwriter) articulated what so many involved in the game were feeling in Time for some (very) civil disobedience.

when the Prime Minister announced on Monday that recreational cricket was not free to go ahead, when we were all free to go into pubs to get pissed, shops to get coughed on and churches to pray in, I must admit that something in me broke. It had threatened to do so for some months, but now it just did.

Writing a week or so later, with club cricket officially sanctioned, Pete Langman (@elegantfowl) found his anticipation of the return to play – The silence of the stands – haunted by the fear of failure: a golden duck

It means we spent more time walking out to bat and back to the pavilion again than we spent in the middle. Dammit, we spent longer donning our protective equipment than we spent on the field.

In unsettled times, the past provides a refuge. The blog ‘Oldebor’ (@sarastro77) is dedicated to cricket before the war. My favourite of its long-form posts this year was the retelling of the story of Douglas Carr, the 37 year-old school master called up for the final Ashes Test of the 1909 campaign.

Where Oldebor does not dwell on the lessons of the past, Stephen Hope (@fh_stephen) draws conclusions from his early memories of the game which he would like today’s administrators to acknowledge – in particular the Sunday League, which “did a more than decent job regenerating the game.. thanks to the Beeb’s coverage and to games played in places that kids could get to. All told it was played on 127 grounds.”

County cricket has come to mean a great deal for @The_Grumbler The silent sanctuary of county cricket soothes this lost soul – but it wasn’t always this way.

Until recently I too considered county cricket as the most wonderful waste of time. Glorious but pointless. Now, in the most difficult period of my life, it has revealed a hitherto hidden purpose as salvation and sanctuary for my troubled mind.

The Full Toss first featured in these annual reviews in 2014. Founder James Morgan has kept the blog fresh, in part by recruiting guest writers. I particularly enjoyed Cameron Ponsonby’s (@cameronponsonby) writing, including an accomplished interview piece about the challenge of facing the fastest bowlers in the game: Watch the ball, play it late, don’t be scared.

Three young cricketers inspired two strong analytical blog-posts. Khartikeya (@static_a357) found a template for the future in the Pooran Way: “Pooran sees the value of his wicket in T20 for what it is. If he gets out attacking, so be it, but the value of hitting sixes in the middle overs outweighs almost everything.” Khartikeya’s argument is strengthened by the conclusion: “..it will all regress to the mean and we will wait for the next Trinidadian superhero to show us the way forward.”

Oscar Ratcliffe (@oscar_cricket) invoked Philip Pullman, Stuart Broad and Steven Smith in assessing the future direction of the careers of Dom Bess and Sam Curran: Showing some mongrel..

There was no lack of quality statistics-based blogging this year. From that genre, I have picked a single piece by Amol Desai (@amol_desai) which took a familiar question – does captaincy affect performance? – and wrung from the numbers (a lot) more insight than Sky Sport’s ex-England captain presenters have managed from their years in post.

Cricket coaching has its own small blogging niche which enables coaches to share ideas and debate best practice. From time-to-time, something of more general interest emerges, as is the case with David Hinchliffe’s (@davidhinchliffe) account of what happened during an indoor session with school age cricketers when one participant said, “I just want to hit balls I don’t care about the game” – All training is compromise..

The final post in the XI is written by someone who would not consider himself to be a cricket blogger, who associates his interest in the game with shame and concludes that he doesn’t really like the sport. But, hey, we welcome all-comers, particularly if they compose entertaining, opinionated cricket-based lists. Clive Barnett (@cliveyb) includes a seasonal message while choosing his top cricket books.

I keep acquiring them thinking that they are likely to be better than they turn out to be, and then disposing of them. It turns out that, unlike dogs, cricket books really are often just for Christmas.

To complement my annual Select XI, I also nominate the ‘World’s Leading Cricket Blogger’ for sustained excellence and entertainment throughout the year. On this occasion, it was a sustained burst of daily blogging from 22 March to the 2 July. Bob Irvine, aka Fantasy Bob (@realfantasybob) was a welcome lockdown companion, with his Witterings covering art, music, the Aberdeen typhoid outbreak of 1964 and every step of pandemic policy – all through the prism of 4th team club cricket in Scotland. Public service blogging.

Direction and misdirection in the field

“Come into the ring,” I shouted to the fielder at deep cover.

“What?”

“Come into the ring.”

“What ring? Where? There isn’t a ring.” Irritation overcoming his initial confusion.

I looked around the in-field, peopled by colleagues in a variety of sporting gear and realised: i) he was right, there wasn’t a one-saving ring recongisable to a cricketer; and ii) even if there had been, he, playing his first ever game of cricket, wouldn’t necessarily have perceived it as ‘a ring’.

“Come closer, closer. That’s it. Stand there.” The annual company cricket match re-started, with my team’s fielders more-or-less occupying the stations to which I had directed them.

I was reminded of this incident reading Matt Becker’s recent post on ‘Limited Overs’ about favourite cricket terms. Matt enthuses about the language of cricket and has enjoyed deciphering it since he started following it from America’s midwest a decade or so ago. For those without an upbringing steeped in the sport, or Matt’s curiosity, the language can be a barrier to engaging with cricket. Fielding positions are particularly arcane.

Not only are the positions colourfully or obscurely named, but their relationship to a spot on the field is imprecise. There is of course a structure to the arrangement of fielders in cricket, but it is looser than, say, in baseball. There are perhaps 20 different fielding position names to describe the placement of fielders spread across up to, in the case of the Melbourne Cricket Ground, 20,000m2. That leaves a lot of room for interpretation.

At the highest level of the game, you will see a fielder receive an instruction from the captain, run to take up a new position, be waved at by the skipper to shift to where the fielder was intended to be stationed and then have their position adjusted again by the bowler. There is a dynamic negotiation over their meaning, ball-by-ball, according to the bowler’s type and intent; the batsman’s orientation, strengths, weaknesses; state of the match and game-specific restrictions.

We also need to take into account differences in grounds, which vary in dimension and may have slopes and hollows, all of which contribute to positions being contingent rather than fixed. It comes, then, with the territory – literally and figuratively. Fielding positions have names, but at least as many understandings of what they mean as there are players on the field.

Here are some of the fielding directions or misdirections that have caught my eye and ear – starting with the misdirections.

Lost in action

At the end of an over, the bowler will, as often as not, head back past the start of their run-up, all the way to the boundary. Their destination, in the game I grew up playing, was long-leg. If the bowler at the other end was particularly swift, or the keeper’s glove-work unreliable, they might be moved closer to the line of the pitch, still on the boundary, to fine leg. Or, if it were a slow-bowler they may be moved in the other direction, to deep backward square (leg).

Somehow, the days of long leg are long gone. The position still exists, but it’s now part of the sweep of boundary occupied by an often not particularly fine fine leg. Cricket seems to have smudged a distinction – between fine and long leg – opting for the former name. No damage done; one fewer comical name for a fielding position.

A significant absence

Third man is probably Test cricket’s most contested over position, despite like Graham Greene’s character of the same name, being largely absent. With fast and medium pace bowlers focusing on the off-stump and outside, it’s a very fruitful scoring zone. Deliveries cut, guided, sliced or edged past slips and gulley fielders will usually run away to the boundary, unless there is a third man in place. For long periods of most innings, there isn’t a third man and runs accumulate and onlookers get bothered. ‘Giving away boundaries,’ is the charge.

Deliberately leaving a gap in the field to tempt a shot is an established tactic. Away-swing bowlers often leave a large gap in the covers to encourage a drive that might end with an edge to slip. Leg-break bowlers may leave mid-wicket unattended to prompt the batter to push in that direction, playing against the spin. I don’t sense this is happening with the absent third man.

It appears to be a signal from the fielding captain of the state of the game. No third-man: we’re OK, don’t mind you having a few boundaries. Third-man in place: time to re-trench. This is logical – the fielder to stand at third-man has to come from somewhere and the move is likely to be defensive.

Depends who’s batting

Deep mid-wicket is a position of distinction. Off-spinners plunder wickets there, defeating quality batters with dip and spin as balls are lofted to the outfield.

Cow corner – although usually just called ‘Cow’ on the field fo play – is where the slogger hits. Captains send a fielder to cow, with resignation, maybe reluctance. The opposition is uncultured, relying on strength not skill.

The role and position are the same. The difference that justifies the alternative names is the perceived technical ability of the batter.

Recreational v professional

By tradition and necessity, the most athletic fielders will tend to field in the covers. It’s a compliment to be asked to field in the covers and a privilege as the ball travels towards you across the square, where the field is most even and reliable.

One of England’s finest cover fielders was Derek Randall, who pursued the ball in the late 1970s and early 1980s with the abandon of a dog chasing a stick in the park . It wasn’t until I went to a Test match and saw that Randall, with Willis or Botham bowling with a new ball, didn’t occupy the covers – that area in front of square on the off-side. He lurked at point, or even backward point, where the hard new ball would more likely be guided. He was always referred to as a cover fielder, even though for that to always be true, it would mean stretching it off the square.

If you position yourself square of the wicket in the opening overs of a professional or good level club game, and focus your eye on the close catchers, first slip will be crouched furthest from the wicket, second slip and keeper will probably be in line with each other. Taking the same position as a spectator at a recreational match, the keeper and the slips will stand in line on a shallow arc. It’s about the speed the ball passes the bat and often the role of the first slip: in recreational cricket an avuncular presence to chivvy and encourage a young ‘keeper, at their shoulder, not from two yards behind them.

Fielding adjustments

Cricket has coped with the imprecision of fielding positions, the need for ball-by-ball negotiation, by developing a language of adjustment. Waving arms and shouts of ‘left, right, back, foward’ could do the job, but there’s a more elegant solution. It is one of my favourite aspects of the language of cricket. It has rules of usage that make it particularly satisfying to employ.

The easiest aspect, although not without its oddity, is the description of how to move a fielder closer or further away from the pitch. ‘Deeper’ contrasts not with ‘shallower’, but with the opposite of longer: ‘shorter’.

Moving fielders laterally (left to right, and vice versa) is really specialised, depending on the fielding position relative to the batter. The principle is of a dial, or clock, and movement around that circle using fixed lines as reference points.

Fielders behind the stumps (e.g. fine leg, third-man) are oriented relative to the line of the pitch, with ‘finer’ used to move them closer to the line of the pitch and ‘wider’ to move in the other direction.

At the opposite end of the field (e.g. mid-on, long-off), the line of the pitch again provides the reference point. In these cases, though, ‘straighter’ denotes a move closer to the line of the pitch, with ‘wider’ again meaning the opposite.

Fielding positions to the side of the pitch use the batting crease as the reference point. To move closer to the imaginary line continuing from the crease, the fielder is instructed to be ‘squarer’. Movement in the other direction depends on the starting point of the fielder. If behind square, ‘finer’; if in front, ‘straighter’.

None of this is essential and much as I savour the particularity of the language, I fully understand that captains are as likely to use cues from the environment to communicate with their fielders: ‘in front of the beer advertisement’; ‘second flag from the scorer’; ‘next to the patch of clover’. Or simply relative to their team-mates: ‘half-way between Ed and Ned’. Finally, there’s always the invitation to the fielder near the bat: ‘as close as you dare.’

A summer with and without cricket

Yesterday’s net had the feel and the taste of an ending. As we stepped onto the outfield and across the newly painted white goal line, no.1 son purred about the conditions for playing football. He shaped to curl a pass that would drop into the path of a team mate.

Yesterday’s net had the feel and the taste of an ending. As we stepped onto the outfield and across the newly painted white goal line, no.1 son purred about the conditions for playing football. He shaped to curl a pass that would drop into the path of a team mate.

The wind tugged at both boys’ lockdown locks as we crossed the field to the nets. But the pleasure no.1 son had taken in the feel of the grass under foot disappeared when he knelt to feel the net surface. The gusts had done little to lift from the astro the moisture from the overnight rain. We dug deep into our bags for old balls, but these were so distended by earlier wet practices, we settled on a couple of pinks, seams raised and colour flaking.

We batted in turn, each soon swiping and thrashing, eschewing the seriousness and urge to improve. Even no.2 son, as angry as a wasp under a glass, when bottled behind helmet and grill at the far end of a net lane, was relaxed.

Barring us, the nets, the field and the clubhouse were empty. Low grey clouds hastened the evening light. In a day or so, no.1 son returns to university. One of his first tasks is to greet the freshers as college cricket captain – skipper of a side he has never played for, its season never having troubled the groundsman, let alone the scorers.

Our protective family bubble has already burst with the return to school of the 1&onlyD and no.2 son. For the male triumvirate, though, this is another cleaving. From mid-March, we have played, laughed and worked out the frustrations of living together with bat and ball. It began with garden cricket, intense and, fierce. In late May, with the back lawn and neighbours’ patience with returning tennis balls, pushed to their limits, there came the blessed relief of nets reopening. On-line booking, hand sanitiser, limits and rules on participants’ relationships, key codes. The very good people of my club doubled down and gifted us, its members, this precious freedom.

Twice weekly, the three of us have netted. The hours of my pre-pandemic commute, recycled into cricket practice. We have contrived matches, set challenges, used video to work on technical details and drifted back to free-form. In forty years of playing, I have never practiced so much.

I must remind myself of the intrinsic value of this experience, because there’s very little to show in terms of improvement. Second ball, yesterday, no.1 son yorked me. Minutes later, I leaped at a half-volley and placed just the finest outside edge on the ball. My younger son later pinned back my off stump, with a ball that (I hope) held its line. No.1 son feels the same about his bowling and his brother’s batting still vacillates. As one shot comes, another goes. It’s some weeks since we last spotted his square cut.

We are fortunate that cricket has been such an active presence this summer. But its absence in other ways still jars. No.1 son, 19, has over-hauled me in his passion for the game, and hasn’t played a single match for college or club. No.2 son was drawn back into cricket’s orbit by the World Cup Final and played at the tail-end of last season. He trained through the winter, netting with the seniors, calculating his chances of a regular fourth team spot and what his playing role might be, eager to make up for his lost season in 2019. Instead, he has two lost seasons, managing just one match last month, when his exposure to school made avoiding cricket matches unnecessary. I don’t have the records to prove it, but I may have broken a streak of 29 seasons, by not taking the field at all this year.

The other absence playing on my mind is no.2 son’s first visit to Lord’s, planned for the Saturday of the Pakistan Test. Our – his, his Grandad and my – intention that this can be rectified in 2021 feels very much in the balance.

That Test was played ten minutes up the road from us, not 200 miles to the south, but would not have been easier to attend if played in Pakistan.

Six Tests in seven weeks might have felt like a feast after the famine of the early summer’s absence of cricket to follow. I really did enjoy both Test series and the white ball stuff that followed it. What puzzled me at the time and still does, is that through May, June and the first week of July, I felt no longing for cricket to view and follow. Like everyone else, I’ve rarely needed the escapism of my favourite sport more, but I adjusted to its absence in the way an addict is not supposed to be capable of doing. I did watch the replays of last year’s World Cup Final and Headingley Test which the broadcasters used to fill hours empty of live action, and experienced again the thrill, but not the frustration of the wider narrative of the game being stalled. When the cricket did return, my old enthusiasm, perhaps buoyed by the presence of both sons, was quickly stoked. The summer with and without cricket has clarified something about my relationship to the game. I feel less dependent, but no less capable of finding profound enjoyment there – Woakes and Buttler, Anderson and Broad, the astonishing Zak Crawley.

In one respect, this summer has done damage to my engagement with the game. I am fortunate to have been able to work from home, maintaining our family’s protective bubble. The keyboard and screen that are my connection to my professional duties are the same that I use to drum out this blog. Returning to the desk at which I have sat all day has had little appeal and so Declaration Game has drifted. I am grateful that it is the only casualty here in this summer with and without cricket.

Lord Ted’s mission to save the tour

The cornerstone of international cricket competition, the Test match tour, has been transformed in recent decades. The pandemic of 2020 has left little in the relationships between nations untouched and it has pushed the international tour to a new extreme. The West Indies are more billeted than on tour: confined to two grounds with hotels on site, with Tests taking place only at those two venues and a single other tour game, contested by two teams made up of their own squad members.

The cornerstone of international cricket competition, the Test match tour, has been transformed in recent decades. The pandemic of 2020 has left little in the relationships between nations untouched and it has pushed the international tour to a new extreme. The West Indies are more billeted than on tour: confined to two grounds with hotels on site, with Tests taking place only at those two venues and a single other tour game, contested by two teams made up of their own squad members.

While change has been recent – the West Indies played eight 3-day tour games in 2000 – the decline of the season-long tour was apparent much earlier. At least it was to those with an eye on cricket’s drift away from forefront of public attention. Ted Dexter had welcomed the introduction of one-day cricket to the English county game in the early 1960s. He led Sussex to the inaugural Gillette Cup final where he managed to defend a total of 169 and then retain the title the following year.

Eight years later, retired from the game (barring some Sunday Leagues appearances), Dexter wrote Wisden’s preview of Australia’s Ashes visit to England in 1972. He acknowledged the bold plan to hold ‘three one-day Tests’ in August, but was concerned that those were the only reference to one-day cricket.

The trouble with the Australian itinerary is that for more than half the time they will be playing what can only be considered friendly games with the counties. Not so long ago this gentlemanly basis of sporting competition was sufficient to keep the crowds amused but with the advent of sponsorship, win-money, man-of-the-match awards, etc., etc., the old format now seems hopelessly outmoded. Honour and glory, artistry and skills are now only given their due by your potential spectator if something depends on the outcome thereof. Not necessarily money; an extra point or two towards some goal may be quite acceptable. On the other hand a dozen or more games following one another in a pattern, each one played in a vacuum as on this tour, gives your cricket fan far too good an excuse to stay away if the weather is poor, if the star players are being rested or for any other minor reason.

The writing was on the wall last time Australia toured England. Since then Illingworth’s team in Australia has signally failed to halt the trend of dwindling gates for State matches. In fact it seemed that neither the State sides nor the M.C.C. could do more than go through the motions when there was literally nothing to play for. In no time at all the lack of interest on the field communicated itself to the watchers and I honestly think they swore to a man that they wouldn’t be taken for suckers a second time.

Surely it is not beyond the wit of man to involve a visiting team in the hurly burly in our own competitions. Points would need to be averaged up to decide how the maverick side was placed in relation to the others — either this or a concerted attempt made to find sponsors to put up prize-money–or, the ultimate in daring, to put up the prizes and promote the matches from within cricket and thus gamble a little on achieving a better return.

Otherwise I fear a situation where already hard-worked county players will be ever more content to take it easy against the tourists; the tourists will be just practising for the Tests and only the hardiest of cricket-watchers will pay to see them do so.

(Wisden 1972, “Welcome Australia”)

It was another seven years before Dexter’s recommendations were addressed. The touring team didn’t get an invitation to the County Championship; nor did cricket put any of its own money at stake to coax interest and excitement from the visitors and their county hosts. But sponsorship was found and Dexter appears to have taken it on himself to secure it.

For those who followed English cricket in the 1970s and 1980s, the names of its sponsors can probably be recalled as easily as those of our political leaders, chart-topping groups and Saturday night television programmes of that era. Gillette, Bensons and Hedges, John Player and Cornhill benefitted from an absence of commercial clutter on the BBC and in the first three cases from being the name of the respective competitions from their introduction. Schweppes, who paid for their name to complement the un-televised County Championship (1977-83), would be a easy-fair standard quiz question.

The name of the sponsor of the 1979 Indian team’s tour matches with the counties is far less well-remembered. Partly, this is because, unlike the other county competition sponsors they were not a household brand, pushing their product in supermarkets and newsagents. It might also reflect the lack of success of the ‘competition’ they sponsored. The name was Holt – not Holt’s the Manchester brewery – but a car care and chemical manufacturer. Wisden in 1979, welcoming the relationship, noted that “The scheme was devised by Ted Dexter and Mr Tom Heywood, chairman of Holt Lloyd International.” In the absence of further detail, I imagine Dexter, former England captain and PR executive, working away at the cricket-enthusiast Heywood until, after one particularly long lunch the corporate cheque book was produced.

That cheque carried the figure of £20,000 (£100,000 in 2020 terms), which would be shared by the Indian touring side and their county opponents, depending on results. The county judged to have given the best performance was awarded a trophy. There were also individual awards for outstanding players. India, across ten county matches, had almost £6,000 to aim for. A county could win £6,000 if it was the only side to defeat the tourists. To place this in its context, the West Indies won £10,000 as World Cup champions in the tournament that immediately preceded India’s tour.

Norman Preston had featured the details of these incentives to the touring team and hosts in his Editor’s notes to the 1979 edition of Wisden. The following year, the Almanack’s coverage of the India tour failed to mention Holt, or the existence of peformance rewards. Preston’s initials are printed at the foot of this tour review. He notes that ten first class games, including three of the Tests, were drawn, that India had a single victory – over Glamorgan – and lost to two counties. Wisden’s encyclopaedic reputation is in this narrow case undeserved.

To find the winners of the Holt Trophy in 1979, I have relied on the Lord’s Museum and its on-line catalogue. Within two folders of material relating to that tour – “Scoresheets, newspaper cuttings, statistics, press releases, correspondence, photographs” – the following examples of content are provided:

Includes spider diagram showing I T Botham’s innings of 137 in the third Test for England vs. India at Headingley, copy of Radio Times article on S M Gavaskar, press release relating to Holt Products’ sponsorship of tourists vs. counties matches, and photographs of the Holt Products Trophy and M J Procter, Gloucestershire captain, receiving the trophy from Holt Products after being chosen as winners of the award in 1979 for the best result against India.

Gloucestershire were the fourth county to play India, with the match at Bristol taking place on July 21-23, one week after England had amassed 633-5dec in their First Test victory. Gloucester fielded a first choice team – Sadiq Mohammed, Zaheer Abbas, Mike Proctor, as well as their home-grown players well-known for their one-day performances. India held the upper hand: underpinned by 137 from Gavaskar, the tourists were 200 runs ahead with Gloucester six wickets down in their first innings and all their overseas players dismissed. Phil Bainbridge and MD Partridge then put on 116 and Proctor declared 100 behind with the former in sight of a maiden ton. In murky light, Proctor took three quick wickets on the second evening and returned the next day to take four more. “Proctor allowed them no respite, bowling below full pace, but to a testing length and line,” Wisden reported on his analysis of 15.3-8-13-7. The home team’s top order then chased down the target of 203 at more than four runs per over.

That must surely have delighted Dexter: a see-sawing game, enterprising captaincy, marquee names performing to a high standard and contributions from county pro’s. Whether the prospect of a bonus had an influence, we don’t know. Nor do we know if the game was well-attended. Scanning the scorecards of the other nine matches, it appears that counties put out strong sides. The tourists came up against: Allan Lamb, Malcolm Marshall, David Gower, Viv Richards, John Wright, Ken McEwan, Clive Lloyd, Clive Rice and Richard Hadlee. Whether they were taking it easy is harder to tell.

Despite Wisden’s silence and India’s lack of success, Dexter’s initiative may have incentivised the counties to make a contest of their tour matches. Gloucestershire and Nottinghamshire were each £3,000 the richer for their efforts. By comparison, Somerset had collected £5,000 for their four match campaign to win the Gillette Cup.

The following year, the West Indies toured and Holt Products continued (or renewed) their sponsorship of the county tour matches. This time there was an eye-catching headline to the deal: the West Indies could net £100,000 if they won each of their 11 first-class county matches. One might wonder if the company bought lottery insurance, or took a calculated risk that such an outcome, faced with motivated opponents and the English weather was improbable. As a twelve year-old, absorbing cricket wherever I could find it, I validate Wisden’s assessment that “interest grew” in the county matches. The existence of the six-figure jackpot is the memory fragment that triggered the research for this article.

The tourists’ quest started, as tradition requires, at Worcester, where they secured a seven wicket victory, with most credit to Malcolm Marshall who took 7-56 in the the home side’s second innings. A curiousity of the game, the description of which takes up almost half of Wisden’s report, concerned Glenn Turner:

Worcestershire were desperately short of resolution in their second innings, which began with an out of character display by Turner, who stepped back and “slogged” at almost every delivery as he made 45 from 24 balls before stepping on to his wicket. The general interpretation was that Turner’s approach was linked with his strong criticism of the West Indians’ conduct on their tour of his native New Zealand in the previous winter. There were also suggestions that he had asked not to be selected for the match because of a back strain. The county’s cricket committee chairman, Mr Roy Booth, later interviewed Turner but an official statement was no more informative than that the club was satisfied that Turner has no grievances with them.

Leicestershire were defeated by an innings inside two days, with Greenidge scoring 165. In the maiden first class match at Milton Keynes, Northamptonshire lost early on the third evening; Richards and Lloyd both recording hundreds. The tourists then paused their challenge to take part in four county one-day matches (Prudential Trophy warm-ups).

Derbyshire, dismissed for 68 in their second innings, were the fourth victims in a nine-wicket defeat. The West Indies moved to Leeds and Lord’s for an international interlude, in the shape of the Prudential Trophy. They had reached the end of May with their hopes of claiming the £100,000 prize alive.

The county challenge was rejoined at Canterbury. A day was lost to rain, but captains Alan Knott and Clive Lloyd made first innings declarations to claw back time. The West Indies bowlers then got to work, dismissing Kent for 84 and setting up a target of 103 which was achieved, not without difficulty, with five wickets down. Another interruption for international cricket followed: the 1st Test at Trent Bridge. The West Indies won a close match by just two wickets. It was both the closest England would come to matching or beating their visitors and yet their only defeat of the series.

The middle game (number six) of the Holt Industries Trophy Challenge was at Hove. More bad weather and, in Wisden’s opinion, “the understrength home side” who had an attack of Imran Khan, Garth le Roux, Ian Greig, Jon Spencer and Geoff Arnold, brought an end to the quest on 16 June.

Three more draws, two rain-affected, left the tourists with a 7-4-0 record, and a string of entertaining innings and incisive bowling performances that entertained spectators immensely and may have raised the sponsor’s profile through radio and newspaper reports of the games.

The following summer, Holt Products again continued (or renewed) their sponsorship of the counties’ games with the tourists: the Australians. I cannot find a record of the incentive structure in place, but it appears not to have motivated the visitors, who managed just two victories. The second of which came late in the summer at Hove, which was again the scene of a significant match in the short life of the Holt Products Trophy. John Woodcock’s Editor’s Notes in the 1982 Wisden were very critical:

Less happily, following a match at Hove in which Sussex fielded a discourteously weak side against the Australians, Holt Products, whose sponsorship had been aimed at making these games between counties and touring teams more competitive, withdrew their support. If Sussex’s action was only partly responsible for Holt’s decision, it was still a pity, in what was a fine season for them, that on this occasion they misjudged their obligations.

Sussex had omitted six players from the team fielded in their previous County Championship match: captain John Barclay, Imran Khan, keeper Ian Gould and bowlers, Garth le Roux, Geoff Arnold and CE Waller. The match fell at the end of the third week of August, one week after the 5th Test at Old Trafford where England’s victory ensured they completed the series turnaround and retained the Ashes. The 6th Test at the Oval was to follow – not only an indulgence, but a dead rubber. Sussex had four matches remaining in the County Championship – a competition they had never won, but for which in August 1981 they were in contention. It appears that they preferred to conserve their star players and captain for that objective. Sussex won all of those four games, but fell two points short of the title which was won by Nottinghamshire.

Sussex were, of course, Ted Dexter’s own county team, which may have made this an uncomfortable denouement to his experiment. Was Dexter critical of his own county’s choice of priority – I suspect not? I also find something odd about Woodcock, a traditionalist, writing so harshly of a county showing such commitment to the County Championship. Barclay wasn’t saving himself and his bowlers ahead of Lord’s final; it was a tough run-in to the first class season that was his focus. The Sussex v Australia game encapsulates the problem Dexter had sought to solve and the dilemma that cricket continues to struggle with: balancing a domestic game with international commitments.

Dexter’s intention had been to incentivise interest and commitment through monetary reward. There is some evidence from these three seasons that the outcome was achieved, but there were also unintended consequences. From the perspective of behavioural economics (1), Dexter’s plan to make the counties’ games with tourists more competitive handed Sussex the permission to be less committed. Woodcock complained about obligations being unfulfilled, but those cultural and emotional ties that bind behaviour are loosened once a financial transaction is introduced. Unwittingly, by offering a performance bonus, Dexter enabled Sussex to, in effect, turn down the financal reward in favour of their other objective.

Touring teams continue to play counties, although with a reducing number of fixtures – Australia met just with Worcestershire and Derbyshire in 2019. The emphasis has shifted to the tourists gaining match practice, but rarely if ever against full-strength opponents. I am not aware of any initiative similar to Dexter’s that would provide context and incentives to perform in these games, whether in England or for Test teams touring other countries. With the benefit of hindsight, Dexter was less a visionary than an unsuccessful conservationist, unable to stem the current of change to international cricket tours.

Note

- See the Haifa Day Care Centre Study, chapter 1, Freakonomics (Steven D Levitt & Stephen J Dubner)

Lockdown cricket (retired hurt)

Even before good sense and Government edict confined us to our homes, sons no.s 1 & 2 and I had transferred our cricket games from the bedroom to the spring-lit back garden. The lockdown finds us in mid-season intensity.

Around 16 metres long, the garden provides just enough space for a pitch. The lawn, assailed from above by years of the boys’ football games and from below by the roots of a thirsty silver birch tree, provides an unpredictable surface. The tennis balls (or the inner cores of incrediballs) jag, leap and creep keeping innings brief and challenging. Modes of dismissal include hitting the ball over a fence, into a fence in an uncontrolled fashion, any edged shot in the direction of an imaginary full umbrella of slips and gulleys and one-hand one bounce. With no counting of runs, deliveries faced is our currency. The leave is highly productive.

The wicket on pitch 1 is the trunk of the maple at the back and centre of the garden. Wear and tear has forced us to pitch 2, where a concrete post provides middle stump, off and middle, leg and middle and we negotiate over whether the off and leg stumps have been hit. Pitch 2 opens up the off-side for the right-hander (sons 1 & 2) and plenty of space for me to nurdle leg-side.

The bowler has a step or two to build momentum. Hitting a good length produces rewards, but the temptation to drop short and see the ball fly past the batter’s chin (or scoot into his ankles) is strong. The pitch takes turn, although it hardly seems worth the effort to rotate a wrist when the natural variation is so.. varied.

Competition, the more so since we have had to spend so much time in each other’s company, is keen. The boys wind each other up, finding fault at every opportunity. They are young men and fling the ball at each other with venom. I flinch, waiting for a catch at short-cover, ready to step in and restore order, should either lad cross the line. No.2 son is particularly incensed that his brother’s criticisms of his technique end up stymying his play. He’s torn: last summer his sibling coached him back into a love of the game; this year, big brother may be trying to undermine him for advantage.

Balls disappear over the three fences and return at a slightly slower rate. Such is the discipline of our batting, it’s rarely the result of a loose shot. A firmly hit back-foot drive can hop next door. Bouncers, flicking arm, shoulder or just climbing over the batter, end up in the allotments behind us. But if it is from a loose drive or a top-edged pull, disdain rains down on the batter as they surrender the crease.

I found another way to leave the crease on Saturday. No.1 son had bowled a spell of off-spin. I had picked him off through the leg-side, forcing him to drop short, which I clattered to the fence (two metres away). He reverted to his stock: seam bowling. A delivery reared off a length, past my face which I turned, only to meet the ball coming back the other way from the concrete post. The tennis ball hit me squarely in the eye.

I spent the rest of the afternoon and evening lying in a darkened room. I had an early night, slept soundly and woke on Sunday with two functioning eyes. I now bat in my non-shatter cycling glasses.

It is a delight to share these games, sometimes good humoured, often intense, with my sons. It lightens the mood of this dark time. But there’s an unease that keeps picking away at me.

No.2 son returned to cricket after England’s World Cup Final win last summer. The junior season had passed and he played three senior matches and netted with his brother in the summer holidays. He has trained through the winter, working hard at senior nets. Cricket, he says, has replaced football as his favourite sport. The summer, this season, has been his goal. Not only may those hopes go unfulfilled, but I worry what shape the recreational game will take when we finally find it safe enough to congregate and spend whole afternoons together.

Catch-up Test Cricket

I have an idea for a change to the Laws of cricket to improve an aspect of Test match play. It would be an attempt to make (even) more Test cricket attractive to watch – more specifically, to restrict those passages of play that don’t feel vital, tense and keenly contested. It centres on competitiveness. For that reason, it goes wholly against the grain of the international game and, I accept, would not be adopted. It’s a political thing, it seems. But the idea came to me not as a challenge to the game’s status quo, but at home.

So, it starts personal: I am no longer always alone watching cricket. My sons join me and with their company comes responsibility and anxiety. Will the cricket.. will England’s performance.. sustain their interest? I’m not really worried about no.1 son. He is in too deep and has found the multiple layers of the sport, which can provide distraction from bad cricket or poor England. No. 2 son is more of my worry. Unlike his brother, he’s not an autodidact. What he knows is what we’re watching and how we interpret it for him. It could go wrong. And for that reason, I want Test cricket to show its better side.

The one aspect that I would change is a function of Test cricket’s tendency for one side’s advantage in a match to be exponential, not linear. This is routinely seen in the margins of victory between two closely matched teams. They are not the handful of runs that, on paper, separate them, but hundreds of runs, with the result and margin often reversed the following week. It’s not the margins of victory themselves that are the problem I want to highlight, but a particular passage of play that occurs as the team in the ascendancy turns their advantage into an unchallengeable lead.

The problem

The recent (2019/20) Trans-Tasman Trophy series was an archetype. In each of the three Tests, Australia held a first innings lead, amounting to 250, 319 and 198 (reduced from 203 after a penalty incurred by Australia in the third innings). From that commanding position, Payne’s team set out to bat again and build their advantage.

The outcome of this tactical ploy is a dissipation of competitive tension throughout the third innings of the match. The fielding team may attack briefly with the new ball, but if incisions aren’t made quickly, the innings proceeds with the teams at arms-length, not locked truly in battle. Runs are accumulated against either bowlers not exerting themselves or second and third string bowlers. The fielding team is trying to slow the scoring – by defensive methods – not in the interests of forcing an error, but simply eating up time, or just plain time-wasting. Batsmen may play attractive innings, but there’s a strong sense of cashing in on the situation rather than shaping the game. The match proceeds, like a car coasting down a hill in neutral – something may happen at the bottom of the hill, but there’s not much propelling it, or standing in its way.

‘Tune in later’, I’d advise a youngster trying to get to grips with Test cricket, ‘when the meaningful stuff starts’, hoping they will bother to return when the fourth innings begins.

A solution in Game Theory?

The problem of one competitor gaining an advantage that is detrimental to the spectators’ experience of the contest is not peculiar to cricket (although the duration of this period might be). From the academic field of game theory has arisen the idea of re-instilling interest in a contest by giving the team that falls behind a catch-up opportunity.

The first example is not just about maintaining competitive tension, but also equity. In football (soccer) knock-out matches that go to penalties, a heavy advantage is enjoyed by the team that kicks first. To level this playing field and promote tighter penalty shoot-outs, it is proposed that the sequence of kicks changes from ABABABABAB to ABBAABBAAB, so each team has the opportunity to take the lead. Baseball is another sport that has received games theory advice. In this case, the recommendation is to vary one of the fundamental components of the sport. The team that leads, it is proposed, should have its innings reduced from three outs, to two outs. This is catch-up theory at its crudest: limiting the scoring opportunities for the team that finds itself ahead. The ideas have not been adopted.

Game theory’s catch-up ideas remain just that. They do, though, provide material that might be applied to Test cricket if we want to rid it of its third innings malaise.

The problem analysed

Before outlining the options available to Test cricket, I have some data on the extent of the problem, drawn from all Test matches in the last decade.

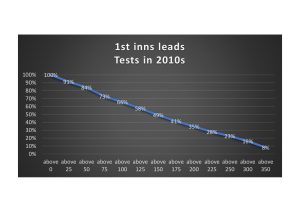

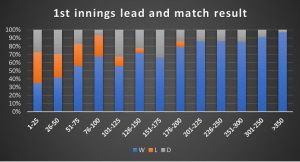

Of the 427 Tests in the sample, almost two-thirds (65.5%) had first innings leads exceeding 100, and more than one-third (34.7%) exceeding 200.

The size of first innings lead closely correlates with the match result. Unsurprisingly, the larger the lead, the greater the prospects of victory and less likelihood of defeat. Once the lead tops 125 runs, the chance of defeat falls below 10%. That threshold is reached even earlier – above 100 – for sides batting first who gain a lead in the initial innings of the match.

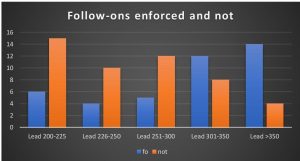

Cricket has, of course, a provision in its Laws to prevent the aimless drift in two-innings matches which feature a dominant side at the half-way point. Law 14 states: “the side which bats first and leads by at least 200 runs shall have the option of requiring the other side to follow their innings.”

21% of the matches in the past decade met the conditions that would enable the side batting first to require their opponents to follow-on. Captains of the side with the advantage opted to do so less than half the time (46%). From the scorecard data, their decision was influenced by the size of their lead, and the number of overs they had they had been in the field to achieve their advantage. Other factors undoubtedly played a part as well: series situation, bowlers’ fitness, weather conditions, etc.

More than one-in-nine Test matches in the 2010s featured a dominant side choose to build-up its lead in an often successful effort to take the sting, the jeopardy and the interest out of the remainder of the game. It’s a significant minority of all matches. Had I not had access to the statistics, I would have guessed the proportion was higher. It seems such a common occurrence – a blight on the sport that has me in its grip.

Catch-up cricket – advantages and disadvantages

I want to argue that if one side establishes a hefty lead, then it is better for the game that the other side bats next – either to bring the game to a swift conclusion, or to straight away challenge the side that has fallen behind to stage a comeback. Either way, all of the cricket is vital and well contested. This is what happens when the side batting second has the hefty first innings lead. These suggestions then, only apply to situations where it is the side batting first that holds the advantage.

I can conceive of a range of options for avoiding the third innings cruise:

- the side with a first innings deficit always bats third

- set an arbitrary first innings lead that would require the side behind to bat third – a return to the mandatory follow-on law

- invert the follow-on rule, so that the captain of the team in deficit decides whether to bat next.

The downside of each of these is the potential for manipulation – gifting runs or wickets to gain a positional advantage: eg allowing the deficit to fall below 200 so that the follow-on isn’t enforced. Let’s park that objection and look at other arguments against forcing the team behind the game back out to the middle to bat again.

There is a strongly held notion that the side that has won the first innings advantage has won the right to determine the sequence of the match – eg avoid batting fourth on a pitch that is likely to be deteriorating. There are political echoes to this understanding of the sport, which I’ll return to later. For now, I’ll restrict my response to noting that this ‘deserved’ advantage may have been the result of a good deal of fortune: winning the toss, batting/bowling in more favourable conditions. More fundamentally, I would counter this objection with the assertion that the sport should be structured to foster competition, not reward a particular team for where they find themselves part-way through the game.

A second argument, which is I suspect more persuasive to the players, is that forcing a side into the field for back-to-back innings risks injuries and fatigue to its bowlers and fielders. The risk is real, but it applies also to the team against whom the opposition amass a score of 500 or more in a single innings over five or six sessions. We expect that fielding captain to manage his or her resources without offering them respite. Shouldn’t we expect the captain of the stronger team – with the sizeable first innings lead – to do the same?

In the knowledge that being the superior team could lead to longer stretches in the field, stronger teams may select more balanced sides, with more bowling options, to drive home the advantage won in the first innings. On winning the toss, they may choose to bowl first, avoiding the possibility of an enforced follow-on, giving the weaker team first use of the pitch. It may change the nature of pitches that home boards task their groundskeepers with preparing. The risk of injury and fatigue is genuine, but so is the ability of cricketers to adapt, possibly in ways that enhance the game.

It can further be argued that the enforced follow-on may shorten games, denying action to spectators with 4th day tickets, advertising revenue for broadcasters and providing sustenance to those wanting to lop a day from the scheduled duration of all Tests. The evidence of the 2010s is that matches where sides with deficits over 200 runs were required to follow-on did wrap up faster – by an average of 50 fewer second innings overs (in excess of half a day’s play). I am not persuaded that we need Tests to be any longer than it takes for one side to dismiss the other twice for fewer runs that it has scored. That is the essence of the sport.

I acknowledged earlier that forcing teams to do something they don’t want to do could bring about match manipulation – gifting of runs or wickets. To assess this risk, it is worth understanding what is at stake for the captain of the side on top, who prefers to bat again rather than enforce the follow-on. There is the concern, already mentioned, about the physical demands on bowlers.

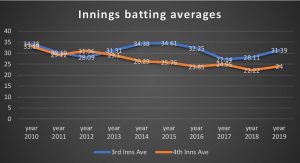

Another factor in that captain’s thinking is wanting to avoid batting last when the pitch conditions will be most difficult for batting. Over the last decade, the fourth innings batting average across all Tests is 4.8 runs per wicket below that for the third innings. Applying that statistic to a first innings lead effectively adjusts a 200 run advantage to 152. It is this sort of calculation that could beget manipulation.

Imagine the team batting second is approaching the (now mandatory) follow-on score: 14 runs (the average 10th wicket partnership in the first innings of the side batting second in the 2010s) short as the ninth wicket falls. The fielding captain could subtly gift those runs to ensure his bowlers get a rest and he avoids the disadvantage of batting last. An average 10th wicket partnership would realise 14 runs, plus the 14 gifted – 28 runs more than the lowest total had the captain managed to take the 10th wicket without conceding any runs. Add four more runs to represent the average partnership score once 14 runs are made: 32. The advantage of batting third over fourth is quickly whittled away.

The reverse argument can be made for the batting team, who may want to manipulate proceedings to maximise their score without passing the mandatory follow-on score. Perhaps both sides would enter an ultra-attacking phase, one willing to risk conceding runs but accepting wickets falling; the other accepting the runs but willing to see their innings close.

It would be an audacious or desperate captain who deliberately reduced their first innings advantage, or increased their deficit. Their control of the degree to which they concede ground to the opposition would not be precise and could just turn out to be match-losing or win-forfeiting. Nonetheless, match-fixing gives us evidence that some players will under-perform for some future or other benefit. If the risk of changing the follow-on law were to introduce the prospect of tactical under-performance in the expectation of creating a superior match situation, it probably wouldn’t be worth it.

An alternative approach would be to leave alone the laws over following-on and innings sequences and take other steps to prevent the third innings drift. This could be done by giving the choice at the outset of the game of whether to bat or bowl, not to the winner of the coin toss, but to the weaker team and trusting them to seek the advantage of batting first (note 1). A number of ways could be employed to identify the weaker team: including the ICC rankings, score to date in the series. I would recommend, at the first test in the series, using away status as a proxy for ‘weaker’. Thereafter, the choice to bat or bowl first would devolve to the team behind in the series, or stay with the away team if the series score were even.

The political dimension

Making the game more competitive in most sports is an issue of equity and entertainment. In international cricket, it is squarely political. In trying to come up with solutions to the third innings malaise, with its passages of play that I would find hard to justify as worth my younger son spending his time watching, I came up against a far stronger barrier than health and safety concerns. International cricket is not run to be competitive. More than that, it is run to be uncompetitive. Catch-up proposals that could, ever so slightly, tilt the balance of a match, have no hope of success when the fabric of the game takes the advantage of some nations, institutionalises it and makes it a matter of active policy. If the health of the wider international sport is not prioritised then it is futile expecting changes that benefit weaker teams mid-match to find any traction.

The nations that participate in international cricket find themselves in the early twenty-first century unequal: population, resources, playing facilities, history, climate, etc. Advantage isn’t truly earned in Test and international cricket. It is an accident of geography, empire, national determination and economic development amongst many other factors. Onto that inequality we graft decision-making authority, match scheduling, access to competitions, distribution of funds and migration of players in ways that entrench relative advantage. But still we praise the strong for exerting their strength and pity the weak for not overcoming their disadvantages. International cricket needs something more fundamental than a catch-up device – a fully-articulated handicap system would be more suitable.

I referred earlier to the objection to the mandatory follow-on that the team with the first innings advantage had earned the right to decide whether or not they would bat next. Underlying it are two ideas that are joined by a golden thread to the politics of international cricket: 1) those with the advantage have decision-making authority; 2) the advantage they hold is deserved. The first idea is base realpolitik and as applied to match-play, relates to nothing intrinsic in the sport. In other words, cricket would lose nothing, if, at the stroke of a pen, the Laws were amended and the authority to decide who bats in the third innings of a match was invested not in the captain of the side with the advantage, but his or her opposite number. The second is the conservative sleight of hand that encourages the status quo to go unexamined: the wealthy and the powerful are deserving of their advantage, when even the shallowest digging below the surface would expose the combination of privilege and good fortune that really accounts for their status.

Back at home

If politics is to continue to prevent cricket becoming the best sport it could be, I don’t think I should shield this fact from my younger son. In future, as a team starts its second innings, aiming just to bloat its already hefty lead in the game, I’ll draw this to No.2 son’s attention. “Look. They have chosen to bat again, to take the game out of reach. It’s what the powerful do: they defend their advantage.”

If Test cricket cannot always be entertaining, let it be educational.

Note 1: for an assessment of the advantage of winning the toss (aka batting first), read criconometrics

A Select XI Blog Posts of 2019

This year’s selection of blog posts is as diverse as each of the previous eight years’ selections, featuring authors from four continents, content spanning the international and recreational game, cricket of the early twentieth century, the modern and near future. There are themes, though: the summer’s World Cup provides material for four pieces; statistical insights inform three and concerns about how the game is run are found in three. The qualification for the Select XI remains that they should be independent and unremunerated writing from the web. Bloggers featured in any of my previous annual round-ups are excluded.

Red Ball Data (@EdmundBayliss) has been one of the pleasures of 2019, providing frequent, ingenious investigations of cricket tactics and performance, with a focus on the red ball game, but in the example I’ve selected, looking at the interaction of one format (T20) with the others: On the decline of Test Batting

To counter-balance the rationalist approach, here is the romantic viewpoint: Mahesh dissects and celebrates a single shot from this year’s Test cricket:

Kusal Perera takes the smallest of strides forward, without the slightest of pretensions to get near the line of the ball, backs his hands to work at his eye’s command, and deposits the ball onto the roof of the stands over extra cover with a most pristine swing of the bat. Dean Elgar pulls down his sunglasses to see how far the ball has gone. Aleem Dar completes the formality of signaling a six but keeps staring towards extra cover as if he is trying to visualise that moment of perfection again.

From this one shot, the author builds an argument for the Six – a shot he describes as unnecessary to Test cricket – as testimony to the adventurous spirit of sports players.

Six appeared on the 81 all out site, alongside my favourite player appreciation of 2019, Yuvraj Singh and the journey from hope to possibility. Aftab Khanna describes the catalysing impact Yuvraj had on the India ODI team of the early 2000s. The core of his success with the bat was having the cleanest of swings:

There was a smooth, unbroken backswing, a stable head at contact, and a clean follow-through with a pristine extension of the arms. In the middle of the cacophony of a packed stadium, Yuvraj brought the tranquillity of the golf course to the art of swinging.

Yuvraj is joined in the Select XI by Wayne Madsen, whose milestone of reaching 10,000 runs for Derbyshire was marked in this affectionately written piece by Steve Dolman (@Peakfanblog).

2019/20 marks the start of the next four year cycle of building towards the 2023 ODI World Cup. Dan Weston (@SAAdvantage) used this as an opportunity to look backwards to the 2019 tournament cycle and forwards to address the personnel changes Pakistan and South Africa would need to make. In Managing the Overhaul, Weston mines his domestic limited overs database to pinpoint which players who could help those nations have more impact in the next World Cup. An article to read, bookmark and review in four years time.

The 2019 World Cup also features in You Couldn’t Write the Script, by Nicholas Freestone. The source of celebration is not simply England’s trip to the final, but the game’s reappearance on free-to-air TV in the UK. Freestone writes about the rise and fall of Channel 4’s cricket coverage, which ran alongside and informed his school days’ fascination with the sport. Days before the final, he concludes:

The sun will be shining on Lord’s and, no matter the result, it will be one of my greatest days as a cricket fan. It was over half my lifetime ago that Channel 4 was showing live England cricket, something that was seminal in my childhood.

Now it is back, and it will be something special – one day in which I can relive the greatest sporting coverage that I will ever see in my lifetime.

Blogging is for amateurs, aspiring professionals and for those who have already made it to the media profession. Peter Della Pena is a CricInfo correspondent, who used his own website to publish an account of watching a World Cup tie with Evan, a friend from his childhood in New Jersey. The Americans watching Afghanistan in England on the 4th of July might not earn Della Pena a paycheck but it makes for a fine, long-form blog, that weaves together a number of themes topical and timeless. Of the latter, there is the insight a cricket watching veteran can gain from accompanying a debutant:

Of all the things Evan could have come across at a cricket match to pique his interest, the Duckworth-Lewis-Stern Method would have been near the bottom of the list of things I would have ever imagined drawing him in. But it happened.

Neil Manthorpe, South African cricket broadcaster, is a dedicated blogger. In recent months he has detailed the crisis in South African cricket governance. My selection comes from the middle of this year: Manners’ reflection on that final in July, notable for its cool detachment as it considers What will the Greatest Final be remembered for?

They [the New Zealand players] held their nerve as well as they held their catches. Time and time again when the intensity of the moment demanded that somebody, or something, should crack, it was not them. They had learned the lesson from the last final, four years ago, when the occasion was too much.

But somebody did crack.

Going back 100 years, the Wisden of 1919 had little cricket to cover and featured obituaries of many players who didn’t make it to the resumption of regular play that spring. For its cricketers of the year, Wisden selected five public school boys. In Whatever happened to? John Winn traced the careers of these five promising youngsters, headed by future England captain, Percy Chapman.

Returning to cricket statistics, an increasingly fertile area for cricket blogging, Playing for Lunch and Tea charts whether batsmen really do alter their play as intervals approach. Karthik’s (@karthiks) exemplary analyses – on this topic and many others – provide eye-catching proof that this truism is statistically supported.

The Club Cricket Development Network (@ClubDevel) is about the only thing I have ever found of value on LinkedIn. It shares experience and good practice on issues that affect club cricket and has taken a representative and lobbying role with the ECB. This piece – The strange death of English cricket – skewers the innumeracy that underlies the grand strategy for the future of the UK’s national summer game and exposes the agenda that makes a particular number attractive to those in authority.

I will end this round-up, in imitation of Wisden, with my nomination of the World’s Leading Cricket Blogger of the Year – aka the blogger whose output has given me most reading pleasure in these last twelve months. Limited Overs is the work of Matt Becker who, from his home in Minnesota, bridges the personal and the global meaning of cricket, with a tender mix of emotion, humour and sincerity. Catching up on Becker’s recent posts, I came across this – characteristic of much of his writing – and apt to use in conclusion of this piece, this year, this decade;

Cricket is an old game. And with that age comes ghosts. And with those ghosts comes weight, and a sense of belonging to something great. I am not sure what that something is. Whether it is time or history or God or the universe. But when we allow ourselves to feel cricket’s ghosts, that is when the game becomes more than a game, and then we have no choice but to keep coming back, to keep that wonderful sense of doleful joy alive in everything we see.

Stokes rediscovered

On Wednesday, I amongst thousands of others will stand and cheer and applaud. It may be at the start of play, or sometime during the day after England’s third wicket has fallen (1). We will be acclaiming Ben Stokes on his return to the cricket field. While I stand, the noise at Old Trafford persisting beyond the span of any normal welcome, I expect the pressure will build on my sinuses, my neck and scalp will become hyper-sensitive and my eyes will prickle. A few deep breaths will probably quell tears. Many in the ground, like me, will have personal reasons that merit such deep emotion, but it will be the sight of England’s bearded, ruddy-faced batting hero that might draw it from us.

2019 is Stokes’s summer. It started with that catch, leaping, back-handed, out of position, in the deep against South Africa. It has surely reached a peak with Sunday’s match-winning, logic-defying century. Its progression from one to the other is well known, its destination in the remaining two Tests is beyond my powers of speculation. The Headingley innings set new standards, but also was a rediscovery.

Returning to England’s line-up last summer, Stokes the batsman was stodgy. Tight matches against India, England’s fragile top-order and the burden of Bristol, we reasoned, were inhibiting him. Stokes’s template innings were Cape Town in January 2016 and Lord’s against New Zealand in 2015. Free-flowing, power batting. The full-face of the bat meeting ball at the apex of its swing. Boundary fielders unable to intercept cuts and back foot drives that travelled just yards to their side; or their heads tilted upwards as sixes soared above them.

“..I’ll probably never bat as well again..” acknowledged Stokes at Cape Town, suggesting a subtlety of character, admitting a tinge of melancholy at a moment of his profoundest triumph. ‘I’ll probably never bat as well again, again,’ Stokes may be reflecting this week. But for all his success in the World Cup campaign there was little to suggest he would rediscover those heights.

Stokes scrapped for runs through the World Cup. He played mature innings, responsive to the match situation. Once, on his previous visit to Old Trafford, the match situation imposed no responsibility. Stokes came to the wicket in the 48th over, after Morgan’s blitz had lifted England above 350. Ball one: fell over, trying to ramp; two: pulled straight to the boundary fielder for a single; three: beaten, nearly stumped; four: dropped cutting; five: swept for a single; six: bowled behind his legs. Meanwhile, Moeen Ali had added two sixes to England’s record number.

Then that innings in the Final. Stokes prevailed, not losing his wicket in regulation time and pressing England’s total forward in the super over. But Stokes had struggled to score. Buttler rotated the strike comfortably in their partnership; Stokes wasn’t able to reciprocate or keep up with the required scoring rate.

As wickets fell and drama piled upon drama, Stokes was being buffeted, swept up in the vortex of cricket’s strangest final. “Why me?”, he seemed to be pleading, anxiety an unfamiliar emotion to read on his face, in place of the stern focus and leonine grin to which we are accustomed. Too good and too lucky to get out; too inhibited by his own form and the circumstance to grasp the match and take England to a clear victory. Stokes give little sense of relishing this challenge. We admired his resilience and, at key moments, his calculation of risk but couldn’t ignore the good fortune that kept the victory within touching distance.

Stokes’s second great innings of the summer differed markedly from the first in the degree of control that he exerted. In the first, events and a live wire opposition had him reeling, but never falling. At Headingley, Stokes was the agent of misrule, upending tactics deployed by the Australians, bending their exertions to his ends. It may simply have been that, when the ninth wicket fell, England’s situation was so desperate that Stokes felt no weight of responsibility. By contrast, England had always remained within sight of victory in the World Cup Final that a single Stokes’ error would have erased.

The ease with which Stokes accelerated at Headingley, achieving a tempo change that eluded him throughout the World Cup, also felt like a rediscovery. The range of shots and his equable response to a misfire – repeating the ramp the very next delivery and hitting it for six – was evidence of a renewed confidence. Not all strokes were cleanly hit – the lofted drives against Lyon travelled over the long-off fielder like ducks winged by hunters. Square of the wicket, though, Stokes was able to reduce the fielders to collecting balls from the other side of the boundary. Most magnificent of all was the back-foot drive to the straight long-on boundary.

Stokes palpably savoured this innings – not that his relish extended to watching Jack Leach batting. If the World Cup Final was, “Why me?”, then Headingley was, “Look at me!”

Ian Botham’s great innings at Headingley was the first of three consecutive match-winning performances. Will this be emulated and the 2019 series be known as “Stokes’s Ashes?” In the aftermath of Headingley, Stokes’s response reminded me not of Botham, but the father-figure of English all-rounders. WG Grace had, reputedly, returned the bails to the wickets, over-ruling the umpires on the field. Stokes, asked about the Lyon’s LBW appeal showed similar certainty. He acknowledged the three reds on the technology before dismissing our modern source of authority, “DRS has got it completely wrong.”

Note:

(1) Weather permitting

Not easily mistaken for

I made my way to the wicket at the fall of the fifth wicket. I took guard, received the conventional information from the umpire and readied myself for the first delivery. As the bowler paused at the top of his run-up, a loud voice from cover point exclaimed:

What? Another leftie?

Hang on. I’m confused. Remind me, which one’s the Saffer international?

The fielder had a fine sense of the ridiculous. The non-striker joined the laughter. My batting partner was Ryan Rickelton, SA junior international: 19 years old, fresh-faced, with a physique developed to excel at his other sport, rugby. I was not and had not. Other than the 22 yards of well rolled and cut turf, Ryan and I only really shared our left-handedness at the crease.

I was reminded of being not easily mistaken for Ryan last week. We had been teammates four years ago, playing a Sunday friendly with a scratch team at Sale CC comprising a few first teamers, some dads and some juniors. The recollection popped up while recording an interview for the podcast ‘81 all-out‘. The host, Subash Jayaraman – aka The Cricket Couch – had paired me with Dan Norcross, creating as unequal a partnership as I had experienced in cricketing matters since Rickelton and I batted together.

Subash wanted to get an English perspective on the World Cup final, in much the same way that the Sale friendly XI skipper had wanted a few lower middle-order runs from his pair of left-handers. My leg-side nudges and edged drives, set against Ryan’s crisp cuts and slog-swept six, can be read across to the contributions Dan and I each made to the podcast. Keep the pro on strike and enjoy the close-up view, I reasoned.

Just as Ryan had time for a mid-wicket chat and ran my singles hard, so Dan allowed space for my more parochial observations and humdrum notions of the greatest ever Cup Final. What I really enjoyed, though, was the thing out of my reach: the straight drive drilled back past me, and away to the tennis courts without losing speed; the fluent linking of multiple ideas, laced with humour and images both jarring and apposite – ‘drowning kittens’; ‘evil Kiwis’ (to have brought such bad fortune upon themselves). The easy, unforced flow of runs and of the spoken word are equally thrilling to witness.

I checked out the scorecard from that Sunday match. I was surprised to see that Ryan scored only five more runs that I had. The bald figures suggest we were closer to parity than I had remembered. But the cover-point fielder was a bringer of truth: I was not easily mistaken for a pro.

Listen to a pro in action here: http://www.81allout.com/world-cup-2019-final-you-win-some-you-tie-some/ You can subscribe to Subash’s podcast at all good pod aggregators, or follow him @cricketcouch

Inhabiting the Eoincene Era

Our day’s first sight of Morgan is well-received. On the big screen in the car-park, he is shown winning the toss – about which we are neutral – and, crucially, opting to bat. He has given his vaunted batsmen an opportunity to pile up runs against the weakest opponents in the tournament. We approve. We have, not a promise, but a probability of a full day of entertainment.

On our second sight, Morgan is less well-received. It’s him tripping down the stairs from the changing room, not England’s greatest limited overs batsman. The innings is in the 30th over. Buttler-time. But Jos is batting in scorecard order, not in situation-specific sequence. ‘Spare your back, skip,’ we mutter. England’s innings, without a Roy-based supercharge, has for 29 overs felt like an preamble, foundations built by a fastidious builder on ground that is already solid and ready for England to erect great towers and arches. Still scoring at 5 runs per over, with wickets in hand – it feels quaint, not bold new England.

Morgan does nothing to alter the tenor – a single off seven deliveries – and we enjoy the replays of Gulbadin’s return catch, taken at shin height, that stopped Bairstow’s progress towards a century and his, as the set batsman, anticipated assault on the bowling. Morgan, like a coach demonstrating the shot to junior cricketers, plays back and forwards with exaggerated care. His bat canted downwards as though surrounded by crouching Afghan fielders. In reality, five are arrayed at the edge of the 30 yard circle and, blue and red kit merging with the World Cup signage, four more are stationed camouflaged on the boundary.

It’s heralded by a no-ball. Morgan pivots on the free-hit and the ball clears the boundary in front of square. Before we know it, the game spirals. Like a boxer, Morgan deals in one-two combinations. Pitch it up and a clean sweep of the bat, sometimes vertical, but always angled optimally for the width of the delivery, sends the ball in gorgeous high arcs beyond the fielders and the straight boundary. Drop it short and Morgan swoops with sudden energy to put the ball beyond the leg side fence.

One-two, one-two.

Morgan’s crouch and his bottom-hand dominant swing enable him to administer lofted drives to half-volleys, good length deliveries and near yorkers.

And there’s variation: the ball angled at his pads is slog swept to the distance; the quicker bowlers driven straight, with the trajectory of powerful artillery. A straighter pull-shot lands in our stand. It feels like a blessing, or coin tossed by the lord of the manor to his underlings.

Morgan may as well levitate, so intense and unreal in its assurance is his shot-making; he sees, he hits. I recall two mishits: the drop on the leg-side boundary and a single air-shot. He also defends, bat straight, with unerring certainty about which is the right ball to attack.

The spell he has fallen under captures us and who knows, maybe the Afghanis, too? For a little over an hour we have eyes, ears and thoughts for nothing else. Time and space are melded: we exist in the Eoincene era, Morganistan. Morgan provides a release, abstracting us from the cares and concerns of our lives, temporarily wiping clear troubled minds. The elation survives his dismissal but is soon gnawed at by guilt, at surrendering to this pleasure in a wider context of angst and discomfort.

One man present remains outside that spell. Root, arriving at the crease twenty overs earlier than his captain, reaches ten after around ten deliveries. He has reached the forties, scored off 40-ish balls when Morgan arrives. A run-a-ball, or thereabouts, through the careful building of foundations, the sudden acceleration of the innings and the sustained hitting. While Morgan has stretched the elasticity of time in a cricket innings, Root was metronomic, rhythmic, maybe detached.

I wasn’t detached. Morgan transported me and, no fault of his own, left me hungover as the real world and its agonies re-established their dominion. I feel sheepish at how readily seduced I was, but in the same measure grateful to have had – and shared – that experience. My memory of it will join other, largely more personal recollections, that I withdraw to, to find respite. Writing this, the day after, provides the same welcome relief.