A select XI cricket blog posts of 2020

How did 2020 affect cricket blogging? Despite there being a lot less cricket played and very much less spectated than most would have planned, we blogged on. For a couple of months in the early summer, our method appeared to have infiltrated the professional media, which switched from match previews and reports to traditional blogging fare: nostalgia, lists and ‘things I would change about cricket’ pieces.

It filled their column inches, but their efforts didn’t really come up to scratch, particularly when compared to the quality output highlighted here. What follows is my personal selection of eleven blog posts from the year. None, to the best of my knowledge, was written for money and none of the writers has been featured in my nine previous annual selections.

It turned out that cricket in the UK found a sweet-spot in 2020, between the first wave of the pandemic and the autumn resurgence. In the early summer, however, it had seemed that the recreational game would be prohibited. The writer and club cricketer, Roger Morgan-Grenville (@RogerMGwriter) articulated what so many involved in the game were feeling in Time for some (very) civil disobedience.

when the Prime Minister announced on Monday that recreational cricket was not free to go ahead, when we were all free to go into pubs to get pissed, shops to get coughed on and churches to pray in, I must admit that something in me broke. It had threatened to do so for some months, but now it just did.

Writing a week or so later, with club cricket officially sanctioned, Pete Langman (@elegantfowl) found his anticipation of the return to play – The silence of the stands – haunted by the fear of failure: a golden duck

It means we spent more time walking out to bat and back to the pavilion again than we spent in the middle. Dammit, we spent longer donning our protective equipment than we spent on the field.

In unsettled times, the past provides a refuge. The blog ‘Oldebor’ (@sarastro77) is dedicated to cricket before the war. My favourite of its long-form posts this year was the retelling of the story of Douglas Carr, the 37 year-old school master called up for the final Ashes Test of the 1909 campaign.

Where Oldebor does not dwell on the lessons of the past, Stephen Hope (@fh_stephen) draws conclusions from his early memories of the game which he would like today’s administrators to acknowledge – in particular the Sunday League, which “did a more than decent job regenerating the game.. thanks to the Beeb’s coverage and to games played in places that kids could get to. All told it was played on 127 grounds.”

County cricket has come to mean a great deal for @The_Grumbler The silent sanctuary of county cricket soothes this lost soul – but it wasn’t always this way.

Until recently I too considered county cricket as the most wonderful waste of time. Glorious but pointless. Now, in the most difficult period of my life, it has revealed a hitherto hidden purpose as salvation and sanctuary for my troubled mind.

The Full Toss first featured in these annual reviews in 2014. Founder James Morgan has kept the blog fresh, in part by recruiting guest writers. I particularly enjoyed Cameron Ponsonby’s (@cameronponsonby) writing, including an accomplished interview piece about the challenge of facing the fastest bowlers in the game: Watch the ball, play it late, don’t be scared.

Three young cricketers inspired two strong analytical blog-posts. Khartikeya (@static_a357) found a template for the future in the Pooran Way: “Pooran sees the value of his wicket in T20 for what it is. If he gets out attacking, so be it, but the value of hitting sixes in the middle overs outweighs almost everything.” Khartikeya’s argument is strengthened by the conclusion: “..it will all regress to the mean and we will wait for the next Trinidadian superhero to show us the way forward.”

Oscar Ratcliffe (@oscar_cricket) invoked Philip Pullman, Stuart Broad and Steven Smith in assessing the future direction of the careers of Dom Bess and Sam Curran: Showing some mongrel..

There was no lack of quality statistics-based blogging this year. From that genre, I have picked a single piece by Amol Desai (@amol_desai) which took a familiar question – does captaincy affect performance? – and wrung from the numbers (a lot) more insight than Sky Sport’s ex-England captain presenters have managed from their years in post.

Cricket coaching has its own small blogging niche which enables coaches to share ideas and debate best practice. From time-to-time, something of more general interest emerges, as is the case with David Hinchliffe’s (@davidhinchliffe) account of what happened during an indoor session with school age cricketers when one participant said, “I just want to hit balls I don’t care about the game” – All training is compromise..

The final post in the XI is written by someone who would not consider himself to be a cricket blogger, who associates his interest in the game with shame and concludes that he doesn’t really like the sport. But, hey, we welcome all-comers, particularly if they compose entertaining, opinionated cricket-based lists. Clive Barnett (@cliveyb) includes a seasonal message while choosing his top cricket books.

I keep acquiring them thinking that they are likely to be better than they turn out to be, and then disposing of them. It turns out that, unlike dogs, cricket books really are often just for Christmas.

To complement my annual Select XI, I also nominate the ‘World’s Leading Cricket Blogger’ for sustained excellence and entertainment throughout the year. On this occasion, it was a sustained burst of daily blogging from 22 March to the 2 July. Bob Irvine, aka Fantasy Bob (@realfantasybob) was a welcome lockdown companion, with his Witterings covering art, music, the Aberdeen typhoid outbreak of 1964 and every step of pandemic policy – all through the prism of 4th team club cricket in Scotland. Public service blogging.

A summer with and without cricket

Yesterday’s net had the feel and the taste of an ending. As we stepped onto the outfield and across the newly painted white goal line, no.1 son purred about the conditions for playing football. He shaped to curl a pass that would drop into the path of a team mate.

Yesterday’s net had the feel and the taste of an ending. As we stepped onto the outfield and across the newly painted white goal line, no.1 son purred about the conditions for playing football. He shaped to curl a pass that would drop into the path of a team mate.

The wind tugged at both boys’ lockdown locks as we crossed the field to the nets. But the pleasure no.1 son had taken in the feel of the grass under foot disappeared when he knelt to feel the net surface. The gusts had done little to lift from the astro the moisture from the overnight rain. We dug deep into our bags for old balls, but these were so distended by earlier wet practices, we settled on a couple of pinks, seams raised and colour flaking.

We batted in turn, each soon swiping and thrashing, eschewing the seriousness and urge to improve. Even no.2 son, as angry as a wasp under a glass, when bottled behind helmet and grill at the far end of a net lane, was relaxed.

Barring us, the nets, the field and the clubhouse were empty. Low grey clouds hastened the evening light. In a day or so, no.1 son returns to university. One of his first tasks is to greet the freshers as college cricket captain – skipper of a side he has never played for, its season never having troubled the groundsman, let alone the scorers.

Our protective family bubble has already burst with the return to school of the 1&onlyD and no.2 son. For the male triumvirate, though, this is another cleaving. From mid-March, we have played, laughed and worked out the frustrations of living together with bat and ball. It began with garden cricket, intense and, fierce. In late May, with the back lawn and neighbours’ patience with returning tennis balls, pushed to their limits, there came the blessed relief of nets reopening. On-line booking, hand sanitiser, limits and rules on participants’ relationships, key codes. The very good people of my club doubled down and gifted us, its members, this precious freedom.

Twice weekly, the three of us have netted. The hours of my pre-pandemic commute, recycled into cricket practice. We have contrived matches, set challenges, used video to work on technical details and drifted back to free-form. In forty years of playing, I have never practiced so much.

I must remind myself of the intrinsic value of this experience, because there’s very little to show in terms of improvement. Second ball, yesterday, no.1 son yorked me. Minutes later, I leaped at a half-volley and placed just the finest outside edge on the ball. My younger son later pinned back my off stump, with a ball that (I hope) held its line. No.1 son feels the same about his bowling and his brother’s batting still vacillates. As one shot comes, another goes. It’s some weeks since we last spotted his square cut.

We are fortunate that cricket has been such an active presence this summer. But its absence in other ways still jars. No.1 son, 19, has over-hauled me in his passion for the game, and hasn’t played a single match for college or club. No.2 son was drawn back into cricket’s orbit by the World Cup Final and played at the tail-end of last season. He trained through the winter, netting with the seniors, calculating his chances of a regular fourth team spot and what his playing role might be, eager to make up for his lost season in 2019. Instead, he has two lost seasons, managing just one match last month, when his exposure to school made avoiding cricket matches unnecessary. I don’t have the records to prove it, but I may have broken a streak of 29 seasons, by not taking the field at all this year.

The other absence playing on my mind is no.2 son’s first visit to Lord’s, planned for the Saturday of the Pakistan Test. Our – his, his Grandad and my – intention that this can be rectified in 2021 feels very much in the balance.

That Test was played ten minutes up the road from us, not 200 miles to the south, but would not have been easier to attend if played in Pakistan.

Six Tests in seven weeks might have felt like a feast after the famine of the early summer’s absence of cricket to follow. I really did enjoy both Test series and the white ball stuff that followed it. What puzzled me at the time and still does, is that through May, June and the first week of July, I felt no longing for cricket to view and follow. Like everyone else, I’ve rarely needed the escapism of my favourite sport more, but I adjusted to its absence in the way an addict is not supposed to be capable of doing. I did watch the replays of last year’s World Cup Final and Headingley Test which the broadcasters used to fill hours empty of live action, and experienced again the thrill, but not the frustration of the wider narrative of the game being stalled. When the cricket did return, my old enthusiasm, perhaps buoyed by the presence of both sons, was quickly stoked. The summer with and without cricket has clarified something about my relationship to the game. I feel less dependent, but no less capable of finding profound enjoyment there – Woakes and Buttler, Anderson and Broad, the astonishing Zak Crawley.

In one respect, this summer has done damage to my engagement with the game. I am fortunate to have been able to work from home, maintaining our family’s protective bubble. The keyboard and screen that are my connection to my professional duties are the same that I use to drum out this blog. Returning to the desk at which I have sat all day has had little appeal and so Declaration Game has drifted. I am grateful that it is the only casualty here in this summer with and without cricket.

Catch-up Test Cricket

I have an idea for a change to the Laws of cricket to improve an aspect of Test match play. It would be an attempt to make (even) more Test cricket attractive to watch – more specifically, to restrict those passages of play that don’t feel vital, tense and keenly contested. It centres on competitiveness. For that reason, it goes wholly against the grain of the international game and, I accept, would not be adopted. It’s a political thing, it seems. But the idea came to me not as a challenge to the game’s status quo, but at home.

So, it starts personal: I am no longer always alone watching cricket. My sons join me and with their company comes responsibility and anxiety. Will the cricket.. will England’s performance.. sustain their interest? I’m not really worried about no.1 son. He is in too deep and has found the multiple layers of the sport, which can provide distraction from bad cricket or poor England. No. 2 son is more of my worry. Unlike his brother, he’s not an autodidact. What he knows is what we’re watching and how we interpret it for him. It could go wrong. And for that reason, I want Test cricket to show its better side.

The one aspect that I would change is a function of Test cricket’s tendency for one side’s advantage in a match to be exponential, not linear. This is routinely seen in the margins of victory between two closely matched teams. They are not the handful of runs that, on paper, separate them, but hundreds of runs, with the result and margin often reversed the following week. It’s not the margins of victory themselves that are the problem I want to highlight, but a particular passage of play that occurs as the team in the ascendancy turns their advantage into an unchallengeable lead.

The problem

The recent (2019/20) Trans-Tasman Trophy series was an archetype. In each of the three Tests, Australia held a first innings lead, amounting to 250, 319 and 198 (reduced from 203 after a penalty incurred by Australia in the third innings). From that commanding position, Payne’s team set out to bat again and build their advantage.

The outcome of this tactical ploy is a dissipation of competitive tension throughout the third innings of the match. The fielding team may attack briefly with the new ball, but if incisions aren’t made quickly, the innings proceeds with the teams at arms-length, not locked truly in battle. Runs are accumulated against either bowlers not exerting themselves or second and third string bowlers. The fielding team is trying to slow the scoring – by defensive methods – not in the interests of forcing an error, but simply eating up time, or just plain time-wasting. Batsmen may play attractive innings, but there’s a strong sense of cashing in on the situation rather than shaping the game. The match proceeds, like a car coasting down a hill in neutral – something may happen at the bottom of the hill, but there’s not much propelling it, or standing in its way.

‘Tune in later’, I’d advise a youngster trying to get to grips with Test cricket, ‘when the meaningful stuff starts’, hoping they will bother to return when the fourth innings begins.

A solution in Game Theory?

The problem of one competitor gaining an advantage that is detrimental to the spectators’ experience of the contest is not peculiar to cricket (although the duration of this period might be). From the academic field of game theory has arisen the idea of re-instilling interest in a contest by giving the team that falls behind a catch-up opportunity.

The first example is not just about maintaining competitive tension, but also equity. In football (soccer) knock-out matches that go to penalties, a heavy advantage is enjoyed by the team that kicks first. To level this playing field and promote tighter penalty shoot-outs, it is proposed that the sequence of kicks changes from ABABABABAB to ABBAABBAAB, so each team has the opportunity to take the lead. Baseball is another sport that has received games theory advice. In this case, the recommendation is to vary one of the fundamental components of the sport. The team that leads, it is proposed, should have its innings reduced from three outs, to two outs. This is catch-up theory at its crudest: limiting the scoring opportunities for the team that finds itself ahead. The ideas have not been adopted.

Game theory’s catch-up ideas remain just that. They do, though, provide material that might be applied to Test cricket if we want to rid it of its third innings malaise.

The problem analysed

Before outlining the options available to Test cricket, I have some data on the extent of the problem, drawn from all Test matches in the last decade.

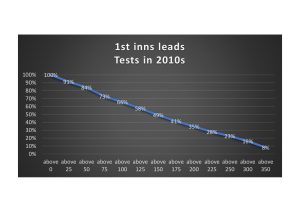

Of the 427 Tests in the sample, almost two-thirds (65.5%) had first innings leads exceeding 100, and more than one-third (34.7%) exceeding 200.

The size of first innings lead closely correlates with the match result. Unsurprisingly, the larger the lead, the greater the prospects of victory and less likelihood of defeat. Once the lead tops 125 runs, the chance of defeat falls below 10%. That threshold is reached even earlier – above 100 – for sides batting first who gain a lead in the initial innings of the match.

Cricket has, of course, a provision in its Laws to prevent the aimless drift in two-innings matches which feature a dominant side at the half-way point. Law 14 states: “the side which bats first and leads by at least 200 runs shall have the option of requiring the other side to follow their innings.”

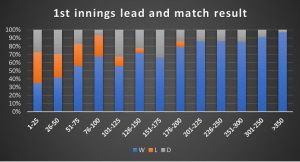

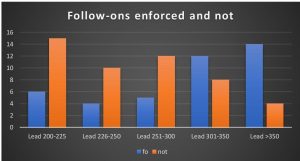

21% of the matches in the past decade met the conditions that would enable the side batting first to require their opponents to follow-on. Captains of the side with the advantage opted to do so less than half the time (46%). From the scorecard data, their decision was influenced by the size of their lead, and the number of overs they had they had been in the field to achieve their advantage. Other factors undoubtedly played a part as well: series situation, bowlers’ fitness, weather conditions, etc.

More than one-in-nine Test matches in the 2010s featured a dominant side choose to build-up its lead in an often successful effort to take the sting, the jeopardy and the interest out of the remainder of the game. It’s a significant minority of all matches. Had I not had access to the statistics, I would have guessed the proportion was higher. It seems such a common occurrence – a blight on the sport that has me in its grip.

Catch-up cricket – advantages and disadvantages

I want to argue that if one side establishes a hefty lead, then it is better for the game that the other side bats next – either to bring the game to a swift conclusion, or to straight away challenge the side that has fallen behind to stage a comeback. Either way, all of the cricket is vital and well contested. This is what happens when the side batting second has the hefty first innings lead. These suggestions then, only apply to situations where it is the side batting first that holds the advantage.

I can conceive of a range of options for avoiding the third innings cruise:

- the side with a first innings deficit always bats third

- set an arbitrary first innings lead that would require the side behind to bat third – a return to the mandatory follow-on law

- invert the follow-on rule, so that the captain of the team in deficit decides whether to bat next.

The downside of each of these is the potential for manipulation – gifting runs or wickets to gain a positional advantage: eg allowing the deficit to fall below 200 so that the follow-on isn’t enforced. Let’s park that objection and look at other arguments against forcing the team behind the game back out to the middle to bat again.

There is a strongly held notion that the side that has won the first innings advantage has won the right to determine the sequence of the match – eg avoid batting fourth on a pitch that is likely to be deteriorating. There are political echoes to this understanding of the sport, which I’ll return to later. For now, I’ll restrict my response to noting that this ‘deserved’ advantage may have been the result of a good deal of fortune: winning the toss, batting/bowling in more favourable conditions. More fundamentally, I would counter this objection with the assertion that the sport should be structured to foster competition, not reward a particular team for where they find themselves part-way through the game.

A second argument, which is I suspect more persuasive to the players, is that forcing a side into the field for back-to-back innings risks injuries and fatigue to its bowlers and fielders. The risk is real, but it applies also to the team against whom the opposition amass a score of 500 or more in a single innings over five or six sessions. We expect that fielding captain to manage his or her resources without offering them respite. Shouldn’t we expect the captain of the stronger team – with the sizeable first innings lead – to do the same?

In the knowledge that being the superior team could lead to longer stretches in the field, stronger teams may select more balanced sides, with more bowling options, to drive home the advantage won in the first innings. On winning the toss, they may choose to bowl first, avoiding the possibility of an enforced follow-on, giving the weaker team first use of the pitch. It may change the nature of pitches that home boards task their groundskeepers with preparing. The risk of injury and fatigue is genuine, but so is the ability of cricketers to adapt, possibly in ways that enhance the game.

It can further be argued that the enforced follow-on may shorten games, denying action to spectators with 4th day tickets, advertising revenue for broadcasters and providing sustenance to those wanting to lop a day from the scheduled duration of all Tests. The evidence of the 2010s is that matches where sides with deficits over 200 runs were required to follow-on did wrap up faster – by an average of 50 fewer second innings overs (in excess of half a day’s play). I am not persuaded that we need Tests to be any longer than it takes for one side to dismiss the other twice for fewer runs that it has scored. That is the essence of the sport.

I acknowledged earlier that forcing teams to do something they don’t want to do could bring about match manipulation – gifting of runs or wickets. To assess this risk, it is worth understanding what is at stake for the captain of the side on top, who prefers to bat again rather than enforce the follow-on. There is the concern, already mentioned, about the physical demands on bowlers.

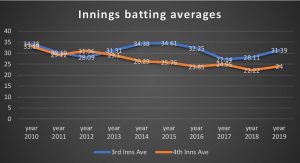

Another factor in that captain’s thinking is wanting to avoid batting last when the pitch conditions will be most difficult for batting. Over the last decade, the fourth innings batting average across all Tests is 4.8 runs per wicket below that for the third innings. Applying that statistic to a first innings lead effectively adjusts a 200 run advantage to 152. It is this sort of calculation that could beget manipulation.

Imagine the team batting second is approaching the (now mandatory) follow-on score: 14 runs (the average 10th wicket partnership in the first innings of the side batting second in the 2010s) short as the ninth wicket falls. The fielding captain could subtly gift those runs to ensure his bowlers get a rest and he avoids the disadvantage of batting last. An average 10th wicket partnership would realise 14 runs, plus the 14 gifted – 28 runs more than the lowest total had the captain managed to take the 10th wicket without conceding any runs. Add four more runs to represent the average partnership score once 14 runs are made: 32. The advantage of batting third over fourth is quickly whittled away.

The reverse argument can be made for the batting team, who may want to manipulate proceedings to maximise their score without passing the mandatory follow-on score. Perhaps both sides would enter an ultra-attacking phase, one willing to risk conceding runs but accepting wickets falling; the other accepting the runs but willing to see their innings close.

It would be an audacious or desperate captain who deliberately reduced their first innings advantage, or increased their deficit. Their control of the degree to which they concede ground to the opposition would not be precise and could just turn out to be match-losing or win-forfeiting. Nonetheless, match-fixing gives us evidence that some players will under-perform for some future or other benefit. If the risk of changing the follow-on law were to introduce the prospect of tactical under-performance in the expectation of creating a superior match situation, it probably wouldn’t be worth it.

An alternative approach would be to leave alone the laws over following-on and innings sequences and take other steps to prevent the third innings drift. This could be done by giving the choice at the outset of the game of whether to bat or bowl, not to the winner of the coin toss, but to the weaker team and trusting them to seek the advantage of batting first (note 1). A number of ways could be employed to identify the weaker team: including the ICC rankings, score to date in the series. I would recommend, at the first test in the series, using away status as a proxy for ‘weaker’. Thereafter, the choice to bat or bowl first would devolve to the team behind in the series, or stay with the away team if the series score were even.

The political dimension

Making the game more competitive in most sports is an issue of equity and entertainment. In international cricket, it is squarely political. In trying to come up with solutions to the third innings malaise, with its passages of play that I would find hard to justify as worth my younger son spending his time watching, I came up against a far stronger barrier than health and safety concerns. International cricket is not run to be competitive. More than that, it is run to be uncompetitive. Catch-up proposals that could, ever so slightly, tilt the balance of a match, have no hope of success when the fabric of the game takes the advantage of some nations, institutionalises it and makes it a matter of active policy. If the health of the wider international sport is not prioritised then it is futile expecting changes that benefit weaker teams mid-match to find any traction.

The nations that participate in international cricket find themselves in the early twenty-first century unequal: population, resources, playing facilities, history, climate, etc. Advantage isn’t truly earned in Test and international cricket. It is an accident of geography, empire, national determination and economic development amongst many other factors. Onto that inequality we graft decision-making authority, match scheduling, access to competitions, distribution of funds and migration of players in ways that entrench relative advantage. But still we praise the strong for exerting their strength and pity the weak for not overcoming their disadvantages. International cricket needs something more fundamental than a catch-up device – a fully-articulated handicap system would be more suitable.

I referred earlier to the objection to the mandatory follow-on that the team with the first innings advantage had earned the right to decide whether or not they would bat next. Underlying it are two ideas that are joined by a golden thread to the politics of international cricket: 1) those with the advantage have decision-making authority; 2) the advantage they hold is deserved. The first idea is base realpolitik and as applied to match-play, relates to nothing intrinsic in the sport. In other words, cricket would lose nothing, if, at the stroke of a pen, the Laws were amended and the authority to decide who bats in the third innings of a match was invested not in the captain of the side with the advantage, but his or her opposite number. The second is the conservative sleight of hand that encourages the status quo to go unexamined: the wealthy and the powerful are deserving of their advantage, when even the shallowest digging below the surface would expose the combination of privilege and good fortune that really accounts for their status.

Back at home

If politics is to continue to prevent cricket becoming the best sport it could be, I don’t think I should shield this fact from my younger son. In future, as a team starts its second innings, aiming just to bloat its already hefty lead in the game, I’ll draw this to No.2 son’s attention. “Look. They have chosen to bat again, to take the game out of reach. It’s what the powerful do: they defend their advantage.”

If Test cricket cannot always be entertaining, let it be educational.

Note 1: for an assessment of the advantage of winning the toss (aka batting first), read criconometrics

A Select XI Blog Posts of 2019

This year’s selection of blog posts is as diverse as each of the previous eight years’ selections, featuring authors from four continents, content spanning the international and recreational game, cricket of the early twentieth century, the modern and near future. There are themes, though: the summer’s World Cup provides material for four pieces; statistical insights inform three and concerns about how the game is run are found in three. The qualification for the Select XI remains that they should be independent and unremunerated writing from the web. Bloggers featured in any of my previous annual round-ups are excluded.

Red Ball Data (@EdmundBayliss) has been one of the pleasures of 2019, providing frequent, ingenious investigations of cricket tactics and performance, with a focus on the red ball game, but in the example I’ve selected, looking at the interaction of one format (T20) with the others: On the decline of Test Batting

To counter-balance the rationalist approach, here is the romantic viewpoint: Mahesh dissects and celebrates a single shot from this year’s Test cricket:

Kusal Perera takes the smallest of strides forward, without the slightest of pretensions to get near the line of the ball, backs his hands to work at his eye’s command, and deposits the ball onto the roof of the stands over extra cover with a most pristine swing of the bat. Dean Elgar pulls down his sunglasses to see how far the ball has gone. Aleem Dar completes the formality of signaling a six but keeps staring towards extra cover as if he is trying to visualise that moment of perfection again.

From this one shot, the author builds an argument for the Six – a shot he describes as unnecessary to Test cricket – as testimony to the adventurous spirit of sports players.

Six appeared on the 81 all out site, alongside my favourite player appreciation of 2019, Yuvraj Singh and the journey from hope to possibility. Aftab Khanna describes the catalysing impact Yuvraj had on the India ODI team of the early 2000s. The core of his success with the bat was having the cleanest of swings:

There was a smooth, unbroken backswing, a stable head at contact, and a clean follow-through with a pristine extension of the arms. In the middle of the cacophony of a packed stadium, Yuvraj brought the tranquillity of the golf course to the art of swinging.

Yuvraj is joined in the Select XI by Wayne Madsen, whose milestone of reaching 10,000 runs for Derbyshire was marked in this affectionately written piece by Steve Dolman (@Peakfanblog).

2019/20 marks the start of the next four year cycle of building towards the 2023 ODI World Cup. Dan Weston (@SAAdvantage) used this as an opportunity to look backwards to the 2019 tournament cycle and forwards to address the personnel changes Pakistan and South Africa would need to make. In Managing the Overhaul, Weston mines his domestic limited overs database to pinpoint which players who could help those nations have more impact in the next World Cup. An article to read, bookmark and review in four years time.

The 2019 World Cup also features in You Couldn’t Write the Script, by Nicholas Freestone. The source of celebration is not simply England’s trip to the final, but the game’s reappearance on free-to-air TV in the UK. Freestone writes about the rise and fall of Channel 4’s cricket coverage, which ran alongside and informed his school days’ fascination with the sport. Days before the final, he concludes:

The sun will be shining on Lord’s and, no matter the result, it will be one of my greatest days as a cricket fan. It was over half my lifetime ago that Channel 4 was showing live England cricket, something that was seminal in my childhood.

Now it is back, and it will be something special – one day in which I can relive the greatest sporting coverage that I will ever see in my lifetime.

Blogging is for amateurs, aspiring professionals and for those who have already made it to the media profession. Peter Della Pena is a CricInfo correspondent, who used his own website to publish an account of watching a World Cup tie with Evan, a friend from his childhood in New Jersey. The Americans watching Afghanistan in England on the 4th of July might not earn Della Pena a paycheck but it makes for a fine, long-form blog, that weaves together a number of themes topical and timeless. Of the latter, there is the insight a cricket watching veteran can gain from accompanying a debutant:

Of all the things Evan could have come across at a cricket match to pique his interest, the Duckworth-Lewis-Stern Method would have been near the bottom of the list of things I would have ever imagined drawing him in. But it happened.

Neil Manthorpe, South African cricket broadcaster, is a dedicated blogger. In recent months he has detailed the crisis in South African cricket governance. My selection comes from the middle of this year: Manners’ reflection on that final in July, notable for its cool detachment as it considers What will the Greatest Final be remembered for?

They [the New Zealand players] held their nerve as well as they held their catches. Time and time again when the intensity of the moment demanded that somebody, or something, should crack, it was not them. They had learned the lesson from the last final, four years ago, when the occasion was too much.

But somebody did crack.

Going back 100 years, the Wisden of 1919 had little cricket to cover and featured obituaries of many players who didn’t make it to the resumption of regular play that spring. For its cricketers of the year, Wisden selected five public school boys. In Whatever happened to? John Winn traced the careers of these five promising youngsters, headed by future England captain, Percy Chapman.

Returning to cricket statistics, an increasingly fertile area for cricket blogging, Playing for Lunch and Tea charts whether batsmen really do alter their play as intervals approach. Karthik’s (@karthiks) exemplary analyses – on this topic and many others – provide eye-catching proof that this truism is statistically supported.

The Club Cricket Development Network (@ClubDevel) is about the only thing I have ever found of value on LinkedIn. It shares experience and good practice on issues that affect club cricket and has taken a representative and lobbying role with the ECB. This piece – The strange death of English cricket – skewers the innumeracy that underlies the grand strategy for the future of the UK’s national summer game and exposes the agenda that makes a particular number attractive to those in authority.

I will end this round-up, in imitation of Wisden, with my nomination of the World’s Leading Cricket Blogger of the Year – aka the blogger whose output has given me most reading pleasure in these last twelve months. Limited Overs is the work of Matt Becker who, from his home in Minnesota, bridges the personal and the global meaning of cricket, with a tender mix of emotion, humour and sincerity. Catching up on Becker’s recent posts, I came across this – characteristic of much of his writing – and apt to use in conclusion of this piece, this year, this decade;

Cricket is an old game. And with that age comes ghosts. And with those ghosts comes weight, and a sense of belonging to something great. I am not sure what that something is. Whether it is time or history or God or the universe. But when we allow ourselves to feel cricket’s ghosts, that is when the game becomes more than a game, and then we have no choice but to keep coming back, to keep that wonderful sense of doleful joy alive in everything we see.

A Select XI blog posts of 2018

This 2018 selection of cricket blog posts features topical issues, stories from the past, the minutiae of the game, insightful numbers, artful descriptions and the deeply personal. All the pieces selected have in common that they are independent and unremunerated writing from the web (note 1).

This 2018 selection of cricket blog posts features topical issues, stories from the past, the minutiae of the game, insightful numbers, artful descriptions and the deeply personal. All the pieces selected have in common that they are independent and unremunerated writing from the web (note 1).

Leading off, we have a measured and expert riposte to the ECB Chairman’s comments about the demise of the junior game. Neil Rollings addresses the question ‘Is Youth Cricket really dying?’ unswayed by nostalgia or any agenda other than giving kids the opportunity to play.

It is not batting and bowling that have become unfashionable, but sitting on the side or fielding in redundant positions. Seeking ever shorter formats does not address this fundamental issue.

Junior cricket and its wider lessons, even if unheeded by the adults who attend games, is the subject matter of a letter written by the 17th Man to his 15 year old nephew (‘Diary of the 17th Man’). Whilst the letter refers to incidents in the young player’s matches, it was written in early April, days after this advice could have averted the year’s biggest cricket drama:

When you are an adult you see how people behave and shift their ideas about what is right or wrong, fair or unfair, depending on the situation or the advantage they can extract from it…

When you know you have done the right thing your conscience is always clear. That is something to cherish.

Blogger ‘Cricket Stuff’ responded to the ECB’s ‘the Hundred’ proposals with a look back at the Lambert and Butler Floodlit Cup, held at football grounds in 1981, concluding: “It had been new, it had been inventive, but it had not been right.” Having introduced Cricket Stuff, I can’t recommend highly enough his work in another medium: the podcast series ‘Cricket and England Through Five Matches’ – a highlight of my cricket consumption this year.

The CricViz initiative made available regular innovative use of game data and quality analytical writing in 2018. While acknowledging the excellence of their work, I have selected a trio of independent statistical posts for this eleven:

- Introducing a T20 captaincy metric: Joe Harris (White Ball Analytics) is a data scientist who makes the most of the compressed and systematic T20 format to explore deep patterns and possible areas of advantage in the short-form game. In this case, Harris proposes a method for measuring the impact skippers make through their bowling changes.

- 1 schoolboy error that even elite batsmen make, also probed an aspect of T20 cricket – specifically, should a batsman try to hit a wide ball? The answer reached by ‘No Pictures in the Scorebook’ is, ‘no’ and in this respect, if no other in 2018, Virat Kohli’s batting was found wanting.

- No place like home, relied on fewer statistical techniques but on Kit Harris’s (@cricketkit) time-consuming research to trace the backgrounds of all 392 professional cricketers in the English county game. The outcome is a picture of the global and local in balance.

Another trio of pieces concerned the game most of us play: recreational, club, mixed age, mixed ability, weekend cricket.

With Quantum of Cricket (‘The Raging Turner’), Liam Cromar relishes the context (playing alongside his old junior coach, six youngsters and a dad), the anticipation and the tiny moments during and around the game (a balanced scorebook!), above all the catch:

The ball starts to die. Staying stationary will result in a half volley. At the last moment, I fall forward to the ground and pouch it at arm’s length a few inches proud. I rise and hold the orb aloft with one hand.

The entire movement forms a perfectly natural, fluid, indivisible quantum of cricket.

The description and the meaning of the moment communicate so clearly why we continue to play, despite age, dubious competence and our busy lives.

It is a theme rendered in verse by Marco Jackson (‘From inside right’): Ode to a Saturday village game. Four stanzas of four lines capture the game and its significance lightly and economically.

‘The Wait’ described by Hector Cappelletti (‘Yahoo over cow corner’), dives deeply into a rarely considered aspect of the game, as true of international players as it is of the club player who is being observed. The no.3 batsman, impatient and anxious, is followed from the the start of the innings until the seventh over when, after expending a lot of nervous energy he finally goes out to bat.

Rounding off the XI are a pair of moving, personal pieces. In 1982 Nick Campion (‘Smell the Leather’) recalls the emotional pinnacle of a dads v lads game of cricket. Nine year old Nick faces his first ball, bowled by his Dad:

I remember as I swung my bat with vigorous abandon being aware that the expected moment of impact had come and gone. There was that awful moment between missing the ball and hearing it hit the stumps when you manage to generate a nanosecond of optimism before the devastating sound of leather on ash crashes through your hopes.

Writer and broadcaster, Cate McGregor provides the most tender and revealing account of cricket’s role in her life. Mystic chords of memory exhibits enormous integrity, while writing so attractively about the difficulties of an extraordinary life.

As a bereaved kid it [cricket] gave me a quiet solace and a respite from bullying. As a trans woman it has given me acceptance and a renewed faith in the goodness of humanity. By choosing to live that night in Adelaide I earned a second innings. I am following on.

With my XI selected, I must make my annual injunction that you should read not just these pieces but other of each bloggers’ material and continue to follow their blogs in 2019.

Finally, my nomination to the accolade (borrowed, of course, from Wisden) of World Leading Cricket Blogger of the Year (note 2). The honour goes to King Cricket. If the King (and his court) is not known to you, may I humbly suggest that you are not doing this cricket blog following thing correctly. Long may he reign.

——–

Note 1: the qualification for the select XI is that the blogger must (to the best of my knowledge) be unremunerated for the post, which must feature on an independent website and the blogger must not have featured in any of Declaration Game’s six previous end-of-year blog post selections.

Note 2: the ‘World Leading Cricket Blogger of the Year’ as a self-consciously over-blown title to award to the blogger whose work I have most enjoyed reading over the previous 12 months. The two past winners are Backwatersman and My Life in Cricket Scorecards.

One day wonder Down Under

The Test series, the Ashes no less, slid away like a fall down a mountainside in a dream. Moments of stability, then another slip, painful scrapes, bruising, but when the bottom came, we were on the whole intact.

When, a little dazed, English minds turned to the one day series, first thoughts were of Moeen even more exposed and Woakes, blinking, but never scowling or swearing, getting carted around the park. Those were the instant notions I had, anyway. But, then, quickly they were chased away by something more upbeat and exciting. Not foresight of Roy’s fast starts, Buttler’s sprint finishes, Wood’s slippery speed or even Rashid’s googly. But the anticipation of an event with associations of its own. Exotic and intense, cricket played on its margins of performance and under lights.

From memory

The source of this thrill felt for limited overs, day-night cricket in Australia, pre-dates Bayliss’s supercharging of the England team, survives the years of plodding competence overcome by Australian boldness, precedes even England’s best team in the world World Cup runners-up of the late 1980s. It springs from the last minute Larry (Kerry?), almost improvised tour of 1979/80.

Australia celebrated peace breaking out between Packer and its cricket board by inviting over their common enemy. England agreed to come and perform as the object of ritual sacrifice before Australia’s united and very strongest team, as long as the Ashes weren’t at stake. There was more wrangling over format with the hosts insisting on Packer’s innovations and the visitors trying to hang onto their dignity, just as they had not given up the urn.

The limited overs internationals fell between and after the Test series that Australia won (without regaining the Ashes). England picked teams for both formats from a single tour party. 38 year old Boycott, naturally, stood aside from the short form games. Until, that was, England found themselves lacking fit batsmen. Boycott, who had made 50 from around 30 overs in the World Cup Final at Lord’s the year before was brought in to open the batting. I suspect he took more pleasure in confounding expectations than he did in his attacking innings of 80-odd, lofting down the ground the bowlers he might preferred to have dead-batted.

It felt that England, despite their recent form as World Cup finalists, were entering a new arena. Floodlit cricket at home meant novelty bashes held on damp nights on a carpet pitch laid over the half-way line at Stamford Bridge. In Australia, light flooded its vast cricket grounds, under spectacular twilight skies. Tens of thousands of passionate, partying Australians, watched from the dark fringes of the ground. The cricket was physical, demanding and unsettling. England, under grey-haired Brearley could get swept away. Their insistence on wearing white marked their naivety and discomfort.

But a single incident showed that England could raise themselves to compete, could be inspired by the novel challenge, not implode sulkily. It was more stunning and memorable even than Boycott lashing Lillee back over his head.

The Australian batsman flashed hard, lifting the ball over the infield. The ball was over the infield, when one of those infielders arched up and backwards, taking the shape of a high-jumper stretching hand first, followed by arm, head and back over the bar. Derek Randall emulated Dick Fosbury’s technique, and surpassed him by catching the ball mid-leap.

That single reflex action showed that England had the vitality and panache to play a full part in the heightened atmosphere of day-night cricket. At home, Randall’s catch was talked about all day before the footage could finally be seen.. on the evening news.

I carry with me the thrill of seeing Randall hurling himself backwards to grasp the ball. It remains dormant until, every four years or so, I think about England taking on Australia in a one-day series, under lights. The whites have gone, as have (usually) the Ashes by then. One day cricket has been normalised. It has been tarted up with rule changes to save the format from itself. End of tour series are derided. Individual matches and performances blend into insignificance. Yet, when this team is playing in a particular country it creates in me an excitement that I can trace back to that one instant.

From the book

England played Australia and the West Indies in a twelve match, three-sided series running from late November until the end of January. Two of the three Test matches between England and Australia fell during the one-day series, the last after the one-day, best of three game finals. West Indies defeated England 2-0 in the finals.

The one-day series began at Sydney on 27 November 1979, where Australia and West Indies contested the first ever ‘official’ ODI under floodlights. The following night, England played the West Indies. Randall’s catch came late in the game. Andy Roberts (not an Australian!) chipped the ball into the leg-side, where Randall launched himself to the ball. England won by two runs, placing all ten fielders (including wicketkeeper Bairstow) on the boundary for the final ball defending three.

England played in their Test match whites. Australia and West Indies wore stylised white outfits, with coloured piping and shoulder panels as well as coloured pads.

Geoffrey Boycott (39) was not selected for England’s first match, but replaced Geoff Miller for the second game, with Brearley dropping to seven in the batting order. Boycott scored 68 (85 balls) in a successful chase of 208. Boycott finished second top scorer in the tournament despite only playing six of a possible nine games with 425 runs (avge: 85), with one century and four 50s. His strike rate (69/100 balls) was higher than that of Gordon Greenidge, Greg Chappell, Alvin Kallicharan and Graham Gooch, amongst others.

A select XI – cricket blog posts 2017

Purpose: to draw attention to the most interesting, insightful and amusing independent cricket writing.

Format: a prose review, structured around a list of eleven selected posts, without clever (or laboured) analogies to the selection of a cricket team.

Criteria: posts published on-line, with authors (to the best of my knowledge) unpaid and having not appeared in any of the five previous Declaration Game annual select XIs. Ultimately, each selection is nothing more than my subjective judgement of what is interesting, insightful or amusing.

The select XI for 2017 begins where almost all cricketers start (and most remain): the grassroots. Being Outside Cricket is a multi-blogger site created by the blogger known as Dmitri Old (select XI 2012). The post ‘Community Service‘ by thelegglance, extols the virtues of club cricket’s dedicated servants before, wholly in keeping with the tenor of the host blog, turning its ire on the cricket establishment:

The rarefied atmosphere of the highest level of any sport is a world away from the day to day that makes up virtually all of the game. Yet professional sport relies on the amateur to a far greater extent than the other way around, even though they both need the other for it to flourish. But take away professional cricket, and the game would survive. Take away amateur cricket and there is simply no game at all, which is why the dismissive behaviour towards it remains one of the more despicable attitudes pervading the corridors of power.

John Swannick moderates a LinkedIn group for club cricket administrators, on which he posted a link to an article by the former Chair of Westinghouse CC. This piece was the most compelling long read of the selected XI. It tells the story of the decline of the club from a thriving institution enjoying on-field success to, within a matter of years, folding.

The warning signs had been creeping into the club for the last four or five years. As players left it became harder & harder to find replacements. As volunteers reclaimed their free time, it became impossible to find others willing to step up. Committee roles became something people recoiled at the thought of.

But as much as we can pinpoint the cause of the apathy, & believe me I do share the feelings of our members, it cannot hide the cold facts. Not enough of our members cared enough about the club to see it through to the end. Too many egos skulked behind rocks & into hiding when a once proud club was relegated not once but twice in the space of a few years. When the time was right to fight for the club & return it to glory, too many seized the opportunity to desert the ship before it sank further.

I doubt any cricket club official in the UK could have read this piece without recognising some aspect of their own club in the meticulously related account of Westinghouse CC’s fall. An uncomfortable, but important read.

A quick change of pace: satire. In the spring, That Cricket Blog wrote a county championship preview, extrapolating the excesses of 2017 to the competition in 20 years’ time – 2037; for example:

Surrey

Background:

Defending champions after another season where bonus points based on corporate hospitality Yelp reviews left on-field performance largely irrelevant.

Dan Liebke has an excellent sense of the ridiculous, which comes across well on Twitter and in the podcasts to which he contributes. I have, though, tended to struggle to get past the sub-title on his liebCricket header (“funny cricket > good cricket”) but was glad I did when he wrote about the end to the 3rd England v South Africa Test.

The tension was immense. A hat trick attempt is always thrilling. A delayed hat trick attempt even more so. A delayed hat trick to win the Test would seem to be just about the pinnacle of Test cricket excitement.

And yet Joel Wilson – a lateral thinking marketing genius disguised as an umpire – found a way to top it.

One of the strongest features of cricket blogs in 2017 was the quality of statistical pieces. Fielding analysis came to the fore. Kesavan trawled through ball-by-ball commentary of 233 Test matches to gather the material for the most comprehensive analysis of slip-fielding that I suspect has ever been published – with breakdowns by bowler type, position, country and individual fielder (Steve Smith and Kane Williamson come out on top).

Paul Dennett had a similar interest and no less an obsession. Dennett introduces Fielding Scores for every player in IPL 2017 thus:

The lack of any worthwhile fielding statistics has always bothered me.

So for this edition of the IPL I tried to do something about it. I’ve spent the last few weeks reviewing every ball of the group stage of the tournament, creating 1,666 entries in a spreadsheet for all the fielding ‘events’.

It has been an absurd amount of fun.

Data visualisation is an adjunct field to statistics and of ever increasing importance. The strongest example I came across in 2017 was the blog post ‘Bat first or field. The choices teams make in Test cricket‘. It uses a background the colour of a Wisden dust jacket, over which charts, maps and monochrome photos slide in and out of view, as the data and its interpretation gradually unfolds.

Charles Davis is a doyen of cricket statisticians, with a prodigious output of analyses, lists and reports on Z-score’s cricket stats blog. One thrust of Davis’s work is to fill the gaps in 19th and early 20th century match records, by using newspaper archives to recreate the detail with which we have only recently come to expect of the recording of international fixtures. In ‘The Odd Fields of the Early Days‘, Davis has surmised, by studying reports in The Times, where the fielders were positioned at the start of the innings in fourteen late 19th century Tests, illustrating how in 1893, Johnny Briggs bowled to a field with five players positioned between mid-off and mid-on.

Raf Nicholson is also a cricket historian, specialising in women’s cricket, and a moving force behind the CricketHER website. In February, Nicholson published her ‘Thoughts on the batter/batsman debate‘. Her contribution is of note not just because of the side she takes, but because of her command of historical source material. The post also very neatly encapsulates one of the challenges facing girls and women’s cricket: whether the game’s growth will come with closer alignment to the men’s game or striking out and creating a distinctively new sport.

Recent history is the subject matter of That 1980s Sport Blog. Steven Pye’s post on the 1984 County Championship was as entertaining as this introduction promises:

The script would involve an underdog who nearly became a hero; a substitute fielder earning himself legendary status for a county that he never played for; panic on the streets of Chelmsford; a case of so near, yet so far for one team, and unadulterated delight for another. There might not be the angle of a love interest, but come the end of September 11, 1984, Keith Fletcher would quite probably have kissed Richard Ollis in relief.

My eleventh choice comes from Matt Becker’s Limited Overs blog. Becker has woven the personal story with the public cricket narrative as effectively and affectingly as anyone. This was hard, it was fun was Becker’s resurfacing after a one year absence from the blog.

And so I came back here. To write about this game I remembered that I loved, and to get away from the book I don’t want to think about anymore, and to keep writing in a space where I feel comfortable.

Becker fulfils that aim throughout the English/US summer of 2017 until, marking the final day of the England v South Africa series, he discloses his motivation for returning to the blog. It is moving and meaningful blogging.

Limited Overs is one of five blogs in the selection – the others are Being Outside Cricket, liebCricket, Z-score’s cricket stats blog and cricketHER – which published regularly during the year and from which selection of a single post was more difficult. I would encourage readers to spend some time visiting each and find their own favourite.

Last year, I introduced – ironically in terms of my appropriating the title, but genuinely in terms of my appreciation of the blog – the World’s Leading Blogger citation, which (as in Wisden) doesn’t restrict me to mentioning those who have not featured in previous years’ Select XIs. I nominated Backwatersman’s New Crimson Rambler and have come very close to announcing his retention of the WLB status for 2017.

Top of the tree, however, as my favourite blog and nomination for World’s Leading Blogger of 2017 is Peter Hoare’s My Life in Cricket Scorecards. Throughout the UK summer, Hoare blogged weekly about the parallel events – cricket and otherwise – of the summer of 1967, when as a young boy he had seen his home county challenge for honours and win the Gillette Cup. The material was fascinating, the writing crisp and the treatment of that earlier time both respectful and questioning. On top of all of that, the delivery through a cricket blog of a sustained project has taken the medium somewhere new and – for anyone with Hoare’s dedication – fertile.

Please read, share, disagree and generally engage with these and the many other independent cricket writers out there on the web.

Context, quality and competitive structure in Test cricket

Cricket, out in the middle, is a visceral sport. Its language captures the physicality that is its essence. Seam, crease, splice, toe, tail, cut, sweep, edge, drop, stump. Concise, direct, as close to concrete as English nouns will get.

Cricket, out in the middle, is a visceral sport. Its language captures the physicality that is its essence. Seam, crease, splice, toe, tail, cut, sweep, edge, drop, stump. Concise, direct, as close to concrete as English nouns will get.

To supplement these words, perhaps because of the multiple levels at which the game can be appreciated, abstract nouns become adopted, semantic shift occurs and great significance becomes attached to them.

Spirit.

Momentum.

Two recent examples. Both show the perils of imprecision innate in abstract notions. Appropriation and assumption lead to dispute and confusion.

A similar process may be happening to the term ‘context’. The word has attained a heightened status in debates about how international cricket can preserve and even develop a broad public appeal. These are important matters to those ardent for the game. Enhancing the ‘context’ of fixtures, in the sense in which the word gets used, may just play an instrumental part in international cricket enduring as a sport with mass appeal.

The vast majority of international cricket is played in bilateral series unattached to a wider competitive structure. Results are jammed into a simple algorithm to create official rankings, but they are treated partly as a thing of curiosity and partly as an irritant.

The ‘context’ argument runs that each match, and cumulatively the sport as a whole, would attract more interest if it had extrinsic value outside of the series currently in progress. Every result should feed into a transparent and finite tally of performance. The absence of this tally is what is meant when international cricket is said to ‘lack context’.

I agree, in that most narrow definition of context. But I disagree with the statement that international cricket lacks context, when the word is given a broader and more natural meaning. And I am unconvinced that feeding every result into a tabulation of teams will do much to alter for the good how cricket is perceived more widely.

International cricket is replete with context. Traditional rivalries need no further explanation. More recently established and rarer contests can quickly gain compelling context. The Oval in 1998 , Chittagong 2016 – famous first victories over England. Each fixture that follows is enhanced for knowing that the traditional order has been upset and will be again. Even drawn matches can be enriched by the history of great rearguards that have dug sides out of intimidating deficits.

Cricket may be unusual for having so little of its interest hanging on the final match result. Individual performances and great passages of play can lodge deeper in cricket’s collective memory than where the match spoils went.

I watched three days of play at Lord’s in 2016. One was heavily animated by the narrow version of context recommended for international cricket. The other two – days three and four of the 1st England v Pakistan Test – were not. There was intrinsic pleasure from the quality of play. On day 3 England’s seamers pushed and probed at the Pakistan batsmen. Day 4, led by Yasir Shah, Pakistan prevailed once Rahat Ali had knocked over England’s top three. And context elevated the spectacle:

- Cook matched Moeen Ali against Misbah, who had batted so freely against him in the series in the UAE the previous autumn. To his second ball, Misbah slog-swept to the Tavern, where Hales completed that most crowd-pleasing activity, the running catch. Remember Brearley running under a skier towards that same boundary 37 years earlier in the second World Cup Final? More context.

- Yasir Shah wasn’t just a leg-spinner baffling England batsmen. He demanded recollection of Abdul Qadir, Warne and Mushtaq who had also floated leggies and googlies past our best batsmen. And there was the context of England’s then looming tour to India and trial by spin.

- The whole match was suffused with the context of Pakistan’s prior visit to Lord’s, Mohammad Amir’s return to Test cricket and Misbah’s career nearing its end.

- From a personal point of view, I had the context of watching day three sitting with my father and older son – a landmark in my cricket-spectating history.

My remaining visit to Lord’s was for the final day of the County Championship. The destination of the title hinged on that day. In support of the narrow definition of context – as the relationship of the match to a wider competitive structure – it drew Lord’s largest crowd for a county championship fixture in decades. It also motivated both teams to pursue a result and so provided a climax fitting for the large crowd.

But the wider competitive framework into which this match fitted, created a day that progressed from combative play where neither side conceded anything in the morning; to a post-lunch drift; which abruptly switched to buffet bowling and unimpeded boundary hitting as the target was set; and ending with both teams throwing everything into achieving a result.

I felt the contrivance sapped the spectacle of meaning. It elevated one context above any others. It could have been the day that Somerset won their first County Championship title, 125 years after joining the competition. They probably would have become champions had the Middlesex v Yorkshire game run its natural course; had the wider competitive context not overrun all other considerations on its final day.

International cricket would gladly welcome record attendances and final day finishes as vindication for upsetting a fashion of organising Test cricket that has developed over more than 100 years. I do not oppose the upsetting of tradition by, in this case, bringing more structure to the game. I also recognise that the context that excited me at the Test at Lord’s is drawn from 40 years of following the sport. Competition, points, positions and qualification can give an additional layer of meaning and make the game more accessible. But bringing those features to Test cricket also presents a risk. I describe three situations, none of which will be the norm, but when they do occur, cricket followers, established and new, are likely to find them unappealing.

England and Australia are tied going into the final Test of the Ashes series. England, owing to results elsewhere are guaranteed a place in the Test Championship play-off; Australia have been eliminated. Both sides approach the match as a dead rubber, which in terms of the overarching tournament, is what it is.

India find themselves in a ‘must win’ match for their hopes of a play-off appearance to stay alive. Pakistan have a grip on the game and set India 440 to win on day five. The match is over by mid-afternoon as the Indian players throw away their wickets in a futile chase rather than opt to battle for a draw against their traditional foe.

South Africa rest key players from the deciding game of a series in Sri Lanka because the points they need to progress in the Championship will be more readily gained by fielding a full-strength team when they return home to face New Zealand.

The competitive context of a Test championship could, at times, damage the competitive value of individual matches. Battles will be sacrificed so wars can be won. There is also the concern that the championship itself may leak credibility owing to its structure. This is most evident in terms of the advantage of playing in home conditions, a benefit that teams have consolidated in recent years. Under the format currently favoured by the ICC, each team will host four series and travel away for another four. While the even balance of home and away play helps the competition’s case, the way those fixtures fall could still drastically skew teams’ prospects. Consider how India’s chances could be affected by these alternative itineraries:

| Option 1 | Option 2 | |

| H v England | A v England | |

| H v New Zealand | A v New Zealand | |

| A v Pakistan | H v Pakistan | |

| A v Sri Lanka | H v Sri Lanka | |

| H v South Africa | A v South Africa | |

| H v Australia | A v Australia | |

| A v Bangladesh | H v Bangladesh | |

| A v West Indies | H v West Indies |

In option 1, India would play just a single series outside of Asia. In the alternative, all their away fixtures are in nations where their players have traditionally struggled to perform to their potential. How credible would a world championship be when a major nation can be given such a leg-up, or be so shackled?

I made the point earlier that the appeal of cricket centres much less on the final result of matches than is the case with other sports. Quality cricket requires no context. Context, in the form of competition, acts as a prop for interest in lower quality fare. As an example, football’s World Cup qualifying campaigns feature many dreary matches, despite the incentive of a finals appearance. “Never mind the performance,” we’re reassured, “it’s the result that matters.”

If those words become associated with the Test Championship, we may look back fondly at the days of bilateral series leading nowhere in particular, but exciting us there and then.

The cricket blogger survey – one year on

Late last year, 104 current and recent cricket bloggers completed a survey. The results enabled me to write about the background and motivation of cricket bloggers; blogging activity and types; and views on future prospects for the pursuit. I had ventured that there would be a fourth post: my own thoughts on future directions for cricket blogging. That has remained unwritten, although some of my ideas will emerge later in this piece. Firstly, though, what has happened to those unpaid cricket writers?

Late last year, 104 current and recent cricket bloggers completed a survey. The results enabled me to write about the background and motivation of cricket bloggers; blogging activity and types; and views on future prospects for the pursuit. I had ventured that there would be a fourth post: my own thoughts on future directions for cricket blogging. That has remained unwritten, although some of my ideas will emerge later in this piece. Firstly, though, what has happened to those unpaid cricket writers?

In late 2014, about one-third of respondents felt they would increase their blog frequency and another third expected it to remain the same – chart below. This I argued, was evidence of energy in the sector, although concerns many mentioned about time available to write made me caution that the plans might not come to pass.

One year on, and it is clear that good intentions have been hard to follow through. The chart below shows a snapshot for the first week of December 2015 of when the most recent post was published on the blog mentioned in the survey response.

Publication frequency in 2015 (for those blogs I was able to locate), compared to that reported for those blogs in the survey is shown below. The blogger attrition rate is 31%, which is over twice the rate expected by survey respondents, with another 20% dropping in publication frequency. (NB this may exaggerate the extent of reduced publishing: I am comparing self-reported frequency in 2014, with counts of posts published in 2015; and bloggers may have based their 2014 self-reports on peak season, not annual averages)

As I emphasised in the survey results posts last year, this is a diverse activity. For some, blogging is a stepping stone to a career. At least four of those whose ‘writing for free’ activity has declined, are involved in professional cricket coverage. Of the 25 who appear to have withdrawn completely from writing about cricket, some are continuing to post on different sites (I am aware of several bloggers who have done this).

In terms of blog type, the largest drop-out rate is found amongst those whose blogs:

- feature essays (i.e. ranging across subjects, often based upon the writer’s personal experience)

- are topical

- had existed for less than one year or 3-4 years

- benefited from fewer than 100 views per day

It is possible that those writers who have given up the pursuit have been replaced by others. A high level of churn is to be expected. I suspect, but cannot prove, that there are fewer independent, unpaid voices. This turnover probably hasn’t curtailed the quantity of blog-type material read on the web. Cricket blogging doesn’t have a very ‘long tail’ (in the Chris Anderson sense), but the turnover has had the effect of docking a few ligaments and sundry strands of the tail. Consolidation within the large sites – particularly cricinfo which continues to add new writers – keeps writing on the web healthy.

Finally, some personal thoughts on what can make a durable cricket blog. Starting with an obvious point: most of the very best writers are still writing. Great prose that describes fresh insight into the sport is the strongest guarantee. More interesting though, is to consider what might make a long-lasting web presence for a keen, if not outstandingly gifted, writer.

My sense is that specialisation has been under-employed. Topical cricket writing is well catered for in the professional media. The personal essay style requires particularly strong writing skills and the ability to connect specific experiences to a general audience if it is to stand out.

I have six suggestions for specialist cricket blogs that I would read. Each requires more refined knowledge that the generalist, and probably some access to sources, but I believe could be written as a dedicated amateur.

Spin bowling – Amol Rajan’s Twirlymen showed the depth of writing this topic can foster. A blog dedicated to spin bowling could meld news (performances of leading players), technical analysis, statistics, history and maybe interviews with players below the mainstream media’s radar.

Umpiring – again, an opportunity for a blog that brings together topical issues, statistics, law interpretation and, surely, high quality anecdotage?

Afghanistan – the most exciting story in international cricket? With a few sources, could there be somebody well placed to collate news, profiles and background stories on this country’s cricket?

Coaching – the importance of work on the practice ground and off the field has never been greater and has never had so many practitioners. Coaching guidance and recommended drills would be welcome, but a site with a broader purpose, debating and promoting the coach’s role would be a strong draw.

South Africa – from the fans’ perspective. I am thinking of something along the lines of, the recently retired, The Full Toss: passionate and opinionated about play, organisation and coverage of the national game

Cricket books – the paper publishing industry careers along. A dedicated blog would have no shortage of willing interviewees, not to mention free review copies.

If the quality of advice is to be judged by the practice of the advice provider, you might want to disregard the above. Declaration Game continues neither because of any notable success, nor owing to expertise in a particular area, but because, as so many bloggers noted in their survey responses last year, writing is reward enough.

Quick single: Early lead

There’s much to be commended in going out and celebrating your team’s victory. Soak up the success; prolong the elevated mood by reconstructing the achievement, bouncing favourite moments off fellow fans.

At home, not quite alone, I am looking forward, as much as backwards. Like the anxious, partisan football fan, who sees his side take an early lead, I think, “No. Too soon. So much time for that other team to mount a come back.” There’s basic psychology at work: a lead means there is something to be lost. Being defeated, without ever being ahead, doesn’t have the discomfort of dashed hopes, the humiliation of squandering an advantage – particularly when, before the contest began, as is the case with England in this Ashes series, I held very slender hopes.

I wanted England to compete, to push the Australians. I hoped this summer that a new bowler of international class would emerge, and two of England’s fresh batsmen would solidify their places. I wanted Cook’s captaincy to be resolved (by which I mean, ended).

Now, though, a vista of opportunity has opened up. But the broader the vista, the deeper the holes into which we can fall. All because of this early lead.

What really complicates things for me is England’s new positive approach to, in particular, batting. Clinging to a one-nil lead throughout a five Test series is not feasible. It used to be. India achieved it in 1982/83 over a six match series: wrangling a first Test victory on a poor pitch and holding out for draws for the rest of the series on pitches where “conditions were so heavily weighted in favour of the bat” (Wisden, 1983). This series will have at least two more results.

I would like England to bat conscious of their lead. I want to see consolidation and conservation applied to their innings. I want context to be recognised and respected.

At the moment, the England middle-order (and one of the openers) seems to believe that attack is the answer to each and every challenge. It worked at Lord’s against New Zealand, and again in both innings at Cardiff.

And it did a thrilling job in the ODI series with New Zealand. But playing without fear isn’t a tactical choice, but a necessity, when it becomes obvious that scoring at seven runs per over is what’s needed to win the game. That’s not the case in Test cricket. While England have found success from playing audaciously on a few occasions, on others they will not.

So far, they have benefited from surprise. If it becomes the default response to the loss of a few early wickets, the Australians will be ready for it and England will show all the calculation of the gambler who doubles his stakes after every loss. England have also been lucky, notably at Cardiff. Root played and missed, edged and squirted the ball past the close catchers. Bell, excluded from the ODI jamboree, appeared determined to show he belonged. His innings featured his classy off-drives – none of which we would have appreciated had any one of his early shots that looped past fielders fallen to hand.

To win a five Test series, a team needs to master a variety of tempos. As a batting line-up, England seem enthralled by a pacey approach, that will soon speed them to defeat, if not used selectively. That’s what I believe – just as I believed in 2005 that Vaughan was reckless and should consolidate gains in that famous Ashes series. My approach to Test cricket was stuck in the past then and maybe similarly out of date now. There’s only one thing for it: can someone take me out to celebrate?