Stokes rediscovered

On Wednesday, I amongst thousands of others will stand and cheer and applaud. It may be at the start of play, or sometime during the day after England’s third wicket has fallen (1). We will be acclaiming Ben Stokes on his return to the cricket field. While I stand, the noise at Old Trafford persisting beyond the span of any normal welcome, I expect the pressure will build on my sinuses, my neck and scalp will become hyper-sensitive and my eyes will prickle. A few deep breaths will probably quell tears. Many in the ground, like me, will have personal reasons that merit such deep emotion, but it will be the sight of England’s bearded, ruddy-faced batting hero that might draw it from us.

2019 is Stokes’s summer. It started with that catch, leaping, back-handed, out of position, in the deep against South Africa. It has surely reached a peak with Sunday’s match-winning, logic-defying century. Its progression from one to the other is well known, its destination in the remaining two Tests is beyond my powers of speculation. The Headingley innings set new standards, but also was a rediscovery.

Returning to England’s line-up last summer, Stokes the batsman was stodgy. Tight matches against India, England’s fragile top-order and the burden of Bristol, we reasoned, were inhibiting him. Stokes’s template innings were Cape Town in January 2016 and Lord’s against New Zealand in 2015. Free-flowing, power batting. The full-face of the bat meeting ball at the apex of its swing. Boundary fielders unable to intercept cuts and back foot drives that travelled just yards to their side; or their heads tilted upwards as sixes soared above them.

“..I’ll probably never bat as well again..” acknowledged Stokes at Cape Town, suggesting a subtlety of character, admitting a tinge of melancholy at a moment of his profoundest triumph. ‘I’ll probably never bat as well again, again,’ Stokes may be reflecting this week. But for all his success in the World Cup campaign there was little to suggest he would rediscover those heights.

Stokes scrapped for runs through the World Cup. He played mature innings, responsive to the match situation. Once, on his previous visit to Old Trafford, the match situation imposed no responsibility. Stokes came to the wicket in the 48th over, after Morgan’s blitz had lifted England above 350. Ball one: fell over, trying to ramp; two: pulled straight to the boundary fielder for a single; three: beaten, nearly stumped; four: dropped cutting; five: swept for a single; six: bowled behind his legs. Meanwhile, Moeen Ali had added two sixes to England’s record number.

Then that innings in the Final. Stokes prevailed, not losing his wicket in regulation time and pressing England’s total forward in the super over. But Stokes had struggled to score. Buttler rotated the strike comfortably in their partnership; Stokes wasn’t able to reciprocate or keep up with the required scoring rate.

As wickets fell and drama piled upon drama, Stokes was being buffeted, swept up in the vortex of cricket’s strangest final. “Why me?”, he seemed to be pleading, anxiety an unfamiliar emotion to read on his face, in place of the stern focus and leonine grin to which we are accustomed. Too good and too lucky to get out; too inhibited by his own form and the circumstance to grasp the match and take England to a clear victory. Stokes give little sense of relishing this challenge. We admired his resilience and, at key moments, his calculation of risk but couldn’t ignore the good fortune that kept the victory within touching distance.

Stokes’s second great innings of the summer differed markedly from the first in the degree of control that he exerted. In the first, events and a live wire opposition had him reeling, but never falling. At Headingley, Stokes was the agent of misrule, upending tactics deployed by the Australians, bending their exertions to his ends. It may simply have been that, when the ninth wicket fell, England’s situation was so desperate that Stokes felt no weight of responsibility. By contrast, England had always remained within sight of victory in the World Cup Final that a single Stokes’ error would have erased.

The ease with which Stokes accelerated at Headingley, achieving a tempo change that eluded him throughout the World Cup, also felt like a rediscovery. The range of shots and his equable response to a misfire – repeating the ramp the very next delivery and hitting it for six – was evidence of a renewed confidence. Not all strokes were cleanly hit – the lofted drives against Lyon travelled over the long-off fielder like ducks winged by hunters. Square of the wicket, though, Stokes was able to reduce the fielders to collecting balls from the other side of the boundary. Most magnificent of all was the back-foot drive to the straight long-on boundary.

Stokes palpably savoured this innings – not that his relish extended to watching Jack Leach batting. If the World Cup Final was, “Why me?”, then Headingley was, “Look at me!”

Ian Botham’s great innings at Headingley was the first of three consecutive match-winning performances. Will this be emulated and the 2019 series be known as “Stokes’s Ashes?” In the aftermath of Headingley, Stokes’s response reminded me not of Botham, but the father-figure of English all-rounders. WG Grace had, reputedly, returned the bails to the wickets, over-ruling the umpires on the field. Stokes, asked about the Lyon’s LBW appeal showed similar certainty. He acknowledged the three reds on the technology before dismissing our modern source of authority, “DRS has got it completely wrong.”

Note:

(1) Weather permitting

Inhabiting the Eoincene Era

Our day’s first sight of Morgan is well-received. On the big screen in the car-park, he is shown winning the toss – about which we are neutral – and, crucially, opting to bat. He has given his vaunted batsmen an opportunity to pile up runs against the weakest opponents in the tournament. We approve. We have, not a promise, but a probability of a full day of entertainment.

On our second sight, Morgan is less well-received. It’s him tripping down the stairs from the changing room, not England’s greatest limited overs batsman. The innings is in the 30th over. Buttler-time. But Jos is batting in scorecard order, not in situation-specific sequence. ‘Spare your back, skip,’ we mutter. England’s innings, without a Roy-based supercharge, has for 29 overs felt like an preamble, foundations built by a fastidious builder on ground that is already solid and ready for England to erect great towers and arches. Still scoring at 5 runs per over, with wickets in hand – it feels quaint, not bold new England.

Morgan does nothing to alter the tenor – a single off seven deliveries – and we enjoy the replays of Gulbadin’s return catch, taken at shin height, that stopped Bairstow’s progress towards a century and his, as the set batsman, anticipated assault on the bowling. Morgan, like a coach demonstrating the shot to junior cricketers, plays back and forwards with exaggerated care. His bat canted downwards as though surrounded by crouching Afghan fielders. In reality, five are arrayed at the edge of the 30 yard circle and, blue and red kit merging with the World Cup signage, four more are stationed camouflaged on the boundary.

It’s heralded by a no-ball. Morgan pivots on the free-hit and the ball clears the boundary in front of square. Before we know it, the game spirals. Like a boxer, Morgan deals in one-two combinations. Pitch it up and a clean sweep of the bat, sometimes vertical, but always angled optimally for the width of the delivery, sends the ball in gorgeous high arcs beyond the fielders and the straight boundary. Drop it short and Morgan swoops with sudden energy to put the ball beyond the leg side fence.

One-two, one-two.

Morgan’s crouch and his bottom-hand dominant swing enable him to administer lofted drives to half-volleys, good length deliveries and near yorkers.

And there’s variation: the ball angled at his pads is slog swept to the distance; the quicker bowlers driven straight, with the trajectory of powerful artillery. A straighter pull-shot lands in our stand. It feels like a blessing, or coin tossed by the lord of the manor to his underlings.

Morgan may as well levitate, so intense and unreal in its assurance is his shot-making; he sees, he hits. I recall two mishits: the drop on the leg-side boundary and a single air-shot. He also defends, bat straight, with unerring certainty about which is the right ball to attack.

The spell he has fallen under captures us and who knows, maybe the Afghanis, too? For a little over an hour we have eyes, ears and thoughts for nothing else. Time and space are melded: we exist in the Eoincene era, Morganistan. Morgan provides a release, abstracting us from the cares and concerns of our lives, temporarily wiping clear troubled minds. The elation survives his dismissal but is soon gnawed at by guilt, at surrendering to this pleasure in a wider context of angst and discomfort.

One man present remains outside that spell. Root, arriving at the crease twenty overs earlier than his captain, reaches ten after around ten deliveries. He has reached the forties, scored off 40-ish balls when Morgan arrives. A run-a-ball, or thereabouts, through the careful building of foundations, the sudden acceleration of the innings and the sustained hitting. While Morgan has stretched the elasticity of time in a cricket innings, Root was metronomic, rhythmic, maybe detached.

I wasn’t detached. Morgan transported me and, no fault of his own, left me hungover as the real world and its agonies re-established their dominion. I feel sheepish at how readily seduced I was, but in the same measure grateful to have had – and shared – that experience. My memory of it will join other, largely more personal recollections, that I withdraw to, to find respite. Writing this, the day after, provides the same welcome relief.

How much is your cricket bat worth to you?

What value do you place on your bat?

What value do you place on your bat?

How much money would you stake on your blade? In our game of bat and ball, the latter come and go. Bats endure. You are in contact with it throughout an innings, crudely as a hitting implement, but more deeply as an ally, an accomplice in your campaign of attack and defence. A fruitless swish and it attracts a disgruntled stare. A stroke to the boundary and the eyes first follow the ball, then return with warmth to assess the bat. In between deliveries, you repeatedly check on the bat, how it is held, weighing it, more attentive than a suitor on a second date. Then you take off for a run and it is your dependant, needing to be carried, slightly slowing your progress until the stretch for the crease and like a clever child it gives you a timely boost. At the non-striker’s end, it’s a stick to lean-on, a pointer to show your team-mate a change in the field, a partner in the dance of shadow-play.

You reach a milestone and it’s your bat you raise to acknowledge your score. How much does its value appreciate when you mark your first fifty or hundred for this team, in this competition, or ever?

Your bat affords you surprising power. Balls sent hurtling away, with little effort on your part, build up your self-regard. Just as easily it undermines you, sending the thinnest of edges to the keeper, or translating your epic swing limply into a looping catch to mid-on. How do you value something so capricious?

You lug your bat to matches, practices and nets. It’s the piece of equipment that doesn’t quite fit in your bag. It catches on doorways, trips up team-mates. Blemishes and cracks appear. The rubber grip shifts down the handle or frays. Your bat needs attention. It’s mortal and replaceable. But at what cost?

I am preoccupied with this question. I have been offered a bat by someone at the club who was themselves given it by a somebody (not a nobody). I’ve been invited to pay what it is worth to me.

Context affects value and now is a good time to be replenishing. I am about to embark on my first full season of weekend cricket in over two decades. Not only might I get a return on a new bat, but with my current bat damaged and neglected I may need to find a replacement by mid-season.

Perhaps unusually for someone with my interest in the game and identification as a batsman, I have scant interest in bat brands and models. Partially, it’s a recognition that I am really not good enough to merit owning a ‘good’ bat – pearls and swine. I also have an intense dislike for the commercialisation of sports equipment that encourages the cost of the logo to exceed the combined cost of the materials and workmanship. I’m a sceptic: aren’t bats priced deliberately to extract the maximum cash that any cricketer is prepared to pay? Their names – evoking nature’s forces and human myths – and their endorsements by professional players are part of the subterfuge?

My recollection of my own bats is imperfect. I can only remember three bats that I have owned: a Slazenger to start off with; an SS Jumbo for a birthday present aged around 12 and my current Woodworm. That must be wrong as that last bat was bought when I returned to club cricket ten years ago. I probably had another Jumbo through the late 1980s to the 2000s, but I can’t remember buying it or burying it.

I bought the bat that now pokes from my cricket bag on-line, seduced by the savings on offer. Untested, it arrived too heavy, but otherwise (!) fitted the bill. I took it to a local cricket equipment shop, who sent it to what I think of as ‘fat bat clinic’. It came back marginally sleeker.

A week ago, the bat without a price was handed over and I was given the chance of a test-drive. It showed few signs of being used. The taping of the edges was preventative, not remedial. ‘Have a go with it at indoor nets and then come back with your price’, I was encouraged.

Last Wednesday night, the bat and I had our trial run. It was a comfortable fit. I put away a couple of meaty cuts. It didn’t help me connect with two sweeps, which I’ve missed all pre-season, or prevent me misreading an out-swinger that looked ready to land on leg-stump, and went on to knock out off. But there was one drive on the up, with no follow-through, that connected high up the blade and skittered back past the bowler. Worth a single, maybe two and probably evidence of a superior bat.

So, what would I spend on a bat; one that isn’t new and probably needs some knocking-in to be match-ready? Ignorant of brands and marques, I went on-line. The particular bat is no longer on sale from the manufacturer. Retailers, though, have stocks. The SE on the label, it becomes apparent means ‘Special Edition’. The bats are being sold with chunky discounts.. but at three or four multiples of what I last paid, and have ever entertained, paying for a bat.

I hop across to eBay. Sellers have ‘nearly new’ versions going for more than twice what I’ve ever spent on a bat. I am faced with a dilemma. The invitation is there to pay what I would value this bat at. The market values this bat at a price that I would not have considered paying. Thoughts spark: what if this is the bat that helps me reach my first ever century? Maybe, wielding this piece of prime English willow, I’ll stop chipping catches to the in-field and will apply myself to play lengthy innings each weekend.

Should I pay what it’s worth to others, or respond to the invitation to pay what it’s worth to me? I already have a bat, albeit one that might not last the season. I don’t genuinely believe that I have unfulfilled potential that a better bat could help me tap into. It would be a luxury, an appealing one, in an area of my life that’s important to me.

I’ve turned this matter over and over. A simple solution has bubbled to the surface. Tomorrow, I will return the bat, commenting on its balance and satisfying middle. I will recommend my club mate sells it on eBay for as much as he possibly can.

Thinking cricket, fast and slow (and sadistically)

Would you prefer a batsman who scores 50 every innings, or one who scores 100 half the time and 0 the rest? The ‘expected value’ (batting average) each player offers their team is the same. The decision appears to rest on whether consistency or the potential for a match-defining innings contributes more to your team.

Jarrod Kimber and Andy Zaltzman discussed this conundrum on a recent episode of the ‘Cricket Sadist Hour,’ acknowledging @analytics_jonas as the source of the riddle. The discussion suggests that there is an answer to the question, if sufficient mathematical heft is applied to it. Indeed there may be, but how often in the real world of cricket, or any other occupation, is a difficult decision subject to rational analysis and resolution?

Suprisingly rarely, according to Daniel Kahneman, Nobel prize winner in Economics and author of ‘Thinking, Fast and Slow’. Kahneman challenged the orthodoxy in the social sciences that, “people are generally rational and their thinking is normally sound.” Kahneman and others put judgement to the test by running experiments. What they consistently found were “heuristics and biases.. the simplifying shortcuts of intuitive thinking.”

Following Kahneman’s lead, I won’t try the tricky statistical enterprise of devising an answer to the question. Instead, I will draw on his book to understand why and in which conditions team-mates, fans or even selectors may choose one of these theoretical batsmen over the other.

Question substitution

The numbers (50, 50, 50, 50… and 0, 100, 0, 0, 100, 100…etc) will play a part in these answers, but to begin with, let’s acknowledge that for most of us, much of the time, decisions are not based on numerical analysis, which Kahneman has shown is too effortful and our brains tend to shun.

This is the essence of intuitive heuristics: when faced with a difficult question, we often answer an easier one instead, usually without noticing the substitution.” Kahneman, p12

Instead of attempting the difficult question (which player, based on their pattern of scoring, and the complex structure of a cricket match, will over time contribute more to the team?), we substitute an easier one. In this case, it might be: “Who scored more runs when I last saw them on TV? or, which player has the purer cover-drive? or, which player is being lauded by the ex-player whose opinion I respect?” Kahneman gives examples of how choices are made over political candidates, investment opportunities and charitable donations, but could easily have added cricket team selection to his list.

I will now engage more directly with @analytics_jonas’s original question but introduce some small aspects of context in order to understand how each of the batsmen might, in different circumstances be our preference.

Experience and memory

Our experience of the two batsmen, aggregated over time, will be very similar (if not identical) in terms of the number of runs we see them score. If decision-making were based on lived experience, we may struggle choosing between the consistent batsman and the success/fail player.

However, studies carried out by Kahneman and other psychologists have shown that decisions are not driven by the lived experience, but by the retained memory of the experience.

The memory that the remembering self keeps.. is a representative moment strongly influenced by the peak and the end. (Kahneman, p383)

Taking the ‘peak’ effect first, the success/fail player will clearly have provided greater peaks to plant in the memory than the steady accumulator of half-centuries. The second aspect, the recency effect works equally well for each as around half the time each of the batsmen will have recorded the higher score in their last innings. Combining the ‘peak effect’ and the ‘end effect’, the success/fail player will have created the more favourable impression.

Prospect theory

Put now in the position of selector opting for one of our two players for the next match, rationally there is nothing to choose between them, as over two innings they are, on average, expected to contribute the same number of runs.

Daniel Bernoulli, Swiss scientist of the eighteenth century, refined this understanding by observing that most people dislike risk. So while the expected value of the two batsmen is the same, there is a premium on the player guaranteed to score 50 each innings (or a discount on his alter ego). For the selector this may make sense. There may be only one innings in the match, so better bank 50 runs than risk 0. Even with two innings, we cannot be certain that our success/fail player won’t make two ducks, before bouncing back to form in a later game.

Kahneman added further nuance to Bernoulli’s theory from the empirically observed standpoint that people’s decisions are context dependent. The pattern found, and stated in Prospect theory, is that the decision-maker whose prospects are poor is more likely to gamble. On the other hand, when faced with a situation that offers only an upside, decision-makers tend to be averse to risk and seize the sure thing.

One-nil down in the series with one match to play, the opportunity of having the century-maker is more appealing. One-up, at the same stage of the series, and the cautious choice is preferred. As explored in a previous post on declaration decisions, when a skipper is on top in a Test match, losing feels worse than winning feels good.

It is important to emphasise that Kahneman’s work is descriptive of the decisions people (Test selectors?) make and not prescriptive of the decisions they should make. Indeed, Kahneman emphasises that these systematic biases, based in this case on decision makers’ reference points (i.e. their context), can create unfavourable outcomes, with good opportunities passed over and poor choices pursued.

Thinking slow

While we wait for advanced cricket analytics to tell us whether absolute consistency trumps its opposite, selectors will have to pick players, pundits will continue to push the interests of their proteges and we followers of the game will invest great hopes in our favourites. By making some effort to examine our preferences we might reveal biases and so move towards more informed selections of, lobbying for and championing of players.

Running catch

Credit: Lord’s TV

Three sudden jarring cries carry the 75 yards from the middle. A pause and then a broader chorus cheers, still high-pitched, but with less urgency. The batsman walks away from the wicket. The chorus members converge from their fielding positions. A wicket has fallen.

How?

Evidence of the eyes: the stumps stand upright, location of bails unclear; the ball has now been returned to the umpire.

Rewind a few seconds. Grab a memory of this, the sixth, sixtieth, perhaps, 360th delivery watched today. Scan for clues: the batsman’s movement, the ball’s destination, keeper’s line, close fielders’ inclined heads.

Apply heuristics of many years of watching, layer with knowledge of the competitors, inject with understanding of the conditions of the pitch and the ball.

Settle on a theory: a thin edge, to a good-length, seaming delivery, gathered to the keeper’s left.

Away to your right, the scoreboard flatly conveys the truth: LAST MAN lbw b 9.

Watching cricket live is a challenge of concentration and observation. The difference between an edge behind, a drive to the boundary or a cautious leave, is found in a fraction of the seconds the ball is live. An experienced eye can make a lot of those fleeting images. But much of the appreciation when watching play at the ground is in the aftermath of the delivery and interpreting the movement of batsmen, fielders and bowler.

There are exceptions, where the key moments of action play out at the same pace as an alert spectator’s attention. My favourite, an incident that can crown any day at the cricket, is the running catch. The usual pulse of action is extended, introducing jeopardy, with just enough time for speculation and ‘will he, won’t he’ thoughts.

The flash of activity that ushers the chance is articulated: an advance down the wicket perhaps, invariably a full swing of the bat that grabs the eye. Following the ball’s course, the brain calibrates trajectory with boundary and deep fielder. Swapping focus, before settling on the fielder, carrying out her own speedy calculations.

While writing, I’m thinking of Damien Martyn ending Kevin Pietersen’s daring first Test innings, Alex Hales (and Moeen Ali) sucker-punching Misbah at Lord’s, a full-length dive at long-on by Cameron Bancroft at a T20 at Cheltenham. None was the most significant moment of that day’s cricket, but each imprinted deeply because I watched them unfold.

The fielder’s athleticism plays a part in the appeal: foot speed to gain ground towards the ball, agility to stretch or even dive to reach it on the full and dexterity to clasp and cling onto the ball while moving at pace. Yet, the running catch that resounds the strongest featured a greying cricketer, most comfortable scheming at slip. But it was from mid-on, in the closing overs of a one-day game, that he pitter-pattered with flat feet down the slope towards the Tavern, like an uncle chasing a paper plate blown away at a family picnic. Mike Brearley, at the 1979 World Cup Final, ran and ran before taking Andy Roberts’ skied pull over his left shoulder.

Imposters at the Sir Leonard Hutton Gates?

Police forces across the world have utilised the tactic of sending invitations to unapprehended criminals to collect prizes. It crossed my mind briefly that I may be being set-up, but I am law abiding, so the ECB invitation to Headingley was more likely to be a wind-up than a set-up. In turn, that anxiety slid into a more familiar one: imposter syndrome.

Police forces across the world have utilised the tactic of sending invitations to unapprehended criminals to collect prizes. It crossed my mind briefly that I may be being set-up, but I am law abiding, so the ECB invitation to Headingley was more likely to be a wind-up than a set-up. In turn, that anxiety slid into a more familiar one: imposter syndrome.

It’s a universal truth that there’s always someone better than you are at cricket. Only the Don is exempt, sitting at the top of that pyramid scheme. It’s almost as true about being a cricket obsessive. In the right environment you’re never more than an anorak away from someone with a finer appreciation of the skills of the game, its history, current players or ‘knowledge ‘ about why that journalist wrote a particular piece about that player. Perhaps it’s only in the security of a blog that one’s obsession reigns supreme.

And coaching, six years after qualifying, remains an area of shifting sands, few solid foundations and ever evolving puzzles. Why can that lad suddenly play that shot? How did that girl develop a throwing arm like that? Why’s that lad suddenly firing the ball down legside? The relationship of my methods and their outcomes are not just disjointed but appear to be on different planes. I am the arch-imposter when coaching.

Attending an event with, amongst others, a current minor counties player, someone who played club cricket with ‘Stokesie’, a county head of coaching and a university head coach reinforced the suspicion, as we gathered by the Sir Len Hutton Gates, that I was a little out of my league.

But inside the ground, sitting square of the wicket, trying to rationalise England’s loss of five top-order wickets to Sri Lanka’s seam attack; attempting to forecast the weather using a mixture of sky-gazing and smartphone apps, brought us all onto a level.

Maybe it was just a day of imposters – out in the middle, not just sat in the crowd. Were England’s top-order shut away in a windowless room in Leeds while a gang of look-a-likes started the English summer for them? Take Alex Hales: leave, leave, leave – no heave. Cook stretching forward, having a dart outside off-stump, when a milestone of run aggregation lay so close by. Root simply failing to be magnificent.

Yet Hales, having made the decision to forego IPL riches, has ample motivation for adopting a new degree of prudence. Earlier this month, against Yorkshire, he accumulated a mere 35 from only five fewer balls than are delivered in an entire T20 innings.

Cook had been characteristically Cooky off his pads. He attempted two off-drives, connected juicily with one, but his edge to the second may make it his last of the summer. And Root bounced to the wicket and played short balls high on the tips of his toes.

Most authentic of all were Stokes and Bairstow. The former banged a few boundaries in defiance of Sri Lanka’s rapid removal of the top order, before bunting a drive to mid-on. Bairstow banged a few balls, too, but it was his energy at the wicket that verified his identity. All but the tightest of singles saw him turning to set off for a second. He charged one 3, when most batsmen would have settled for 2, and had to be sent back from attempting an all-run 4.

Another England batsman made a fine impression. Mark Ramprakash was walked across the ground at lunch to greet the award-winning coaches, treating each, whether genuine or imposter, with quiet congratulations and wishes for a enjoyable day.

My cover wasn’t blown, or my company were too polite to out me. In truth, I had had a narrow escape – not at Headingley though, but at the conference I was to attend before I received the ECB’s generous invitation. I was to share my expertise on transforming contact centres. Imposter alert!

Do breaks in play take wickets?

It seems uncontroversial to state that batsmen are more likely to be dismissed immediately after an interval, than when they have settled back into the new session. But similarly well-worn aphorisms – the nervous nineties and batsmen tending to fall quickly after sharing a sizeable partnership – have shown not to stand up to statistical scrutiny. This post, therefore, attempts to apply numerical analysis to the received wisdom that in Test matches batsmen are more vulnerable immediately after resuming play.

Before introducing the numbers, it’s worth reflecting why this common understanding is so readily accepted by cricket followers. I think there are two mutually reinforcing factors at play, each of which could be supported by associated statistical evidence.

The first factor is that batsmen are at their most vulnerable early in an innings. Owen Benton, in his post ‘When is a batsman ‘in’?‘ demonstrated that the likelihood of a Test opening or middle order batsman falling before scoring another five runs is at its highest when on a score below five. It can be argued that this early-innings fallibility revisits the batsman in the analogical position of re-starting an innings after a break in play.

The second factor is that it is accepted good tactical practice for the fielding side to start the session with its most potent bowlers. While there are no statistics to hand to demonstrate that this tactic is actually applied regularly, nor that those bowlers are more threatening immediately after a break, it would be straightforward to compare the career strike rates of the bowlers opening after the resumption against other bowlers used in that innings.

To test the proposition that wickets fall more frequently after a break in play, I selected a random sample of Test matches played since May 2006 (the date from which cricinfo.com scorecards recorded the score at every break in play). Details on the sampling method are provided at the foot of this post.

From the sample of 20 Tests, I noted the incidence of wickets falling in the three overs following (and prior to) 436 breaks in innings, including lunch, tea, drinks breaks, close of play and weather interruptions. Excluded from this figure are any breaks which coincided with the start of a team’s innings.

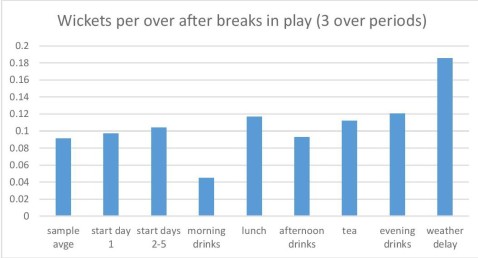

All results are strike rates expressed as wickets per over. In the period 2006-2015, wickets fell on average in Test cricket at 0.08 per over. As the chart below depicts, there was a 50% increase in the strike rate in the first over after a break in play (0.125). This effect wore off rapidly, so that the second over after the resumption saw a strike rate (0.090) that was barely above the period average and equivalent to the sample average (0.091).

The result for the 1st over after a break in play is statistically significant. The sample size doesn’t enable the analysis by type of break in play to be anything other than indicative, but is presented below for interest – based upon the first three overs of the restart.

Weather breaks appear to be the most damaging to a batsman’s prospects, but the 20 Test sample only featured 11 weather breaks. There does not appear to be any relationship to the duration of the break. For example, the overnight break was associated with a lower strike rate than the brief evening drinks break.

The sample results do seem to bear out the received wisdom that batsmen are vulnerable immediately following a break in play. However, the brevity of the impact – a single over – doesn’t strongly support the two explanations offered above.

If batsmen find a new session is like starting a new innings, then the effect would be visible in the second over, as six deliveries is unlikely to be sufficient for both batsmen to pass this phase.

If the phenomenon is caused by the more potent (and refreshed) bowlers, it too would be discernible in the second over (bowled by the other fresh strike bowler) and third overs of the new session.

There remains an explanation and it’s a prosaic one, which will often be used by commentators seeing a batsman fall soon after a break. It may simply be that the batsman’s concentration has been interrupted and not sufficiently refocused for that first over of the restart. There’s a message here for players – prepare psychologically for the new session – and spectators – don’t dither, get back to your seat for the restart.

——————————-

Sampling method:

383 Test matches were played in the period from May 2006. Based on an estimated 9,000 breaks in play with an expected strike rate per 18 deliveries of 0.3, 478 breaks in play were needed to give a result with confidence interval of 0.04 at a 95% confidence level. Excel’s random integer function was used to pick numbers between the Test match references of the first (1802) and last (2181) in the sample period. It is worth noting that the random sample was based on Test matches, not breaks in play.

Using the number of relevant breaks in play from the 20 Test sample, a lower total number of breaks of play in the population was calculated for the population of Tests: 8,600. The adjusted sample size was 417, which is lower than the sample on which data was collected.

The psychology of pundits’ predictions

As the South Africa v England series approaches, the pundits and correspondents will roll out their predictions. The most predictable thing of all will be the shape of those predictions. Beefy, Nass, Boycs, Corky and co will fancy England’s chances to steal a rare away win. Polly, Kepler, Fanie, etc will be confident that the home team will bounce back from its defeat in India and prevail over England.

As the South Africa v England series approaches, the pundits and correspondents will roll out their predictions. The most predictable thing of all will be the shape of those predictions. Beefy, Nass, Boycs, Corky and co will fancy England’s chances to steal a rare away win. Polly, Kepler, Fanie, etc will be confident that the home team will bounce back from its defeat in India and prevail over England.

I have always assumed that this partisan predicting of the outcome of a close contest is somehow an artifice of being a media voice: it would be disloyal to downplay your country’s team; or poor form to admit on your host broadcaster that ‘our team’ won’t win and so the game might not be attractive to watch. It could be an extension of the “conviction, clarity of thought, even blind faith” that Ed Smith has identified as necessary in the elite sportsman, but trips up those same individuals when they climb the steps to the commentary box.

It turns out, however, that there may be something a little more subtle at work (footnote 1). Psychologists have found that however rationally we may believe we are behaving, we have difficulty separating what we want to happen from what we predict will happen. It’s not hard to see how those two concepts get confused when an individual is emotionally involved in the outcome – as a cricket follower is in the fortune of her team. But experiments show that it’s a stickier phenomenon than that.

In tests (the pseudo-laboratory kind found in experimental psychology, not that kind of test that stands at the pinnacle of cricket) participants have been given a role to play and then predict the outcome of a related event. Their predictions have been influenced by the role they were asked to assume; and that influence is in the direction of being more favourable to their temporarily adopted identity. Even when a financial reward was made available for the accuracy of the prediction, participants were inclined to over-egg the likelihood of the outcome that aligned with the role they played.

I imagine it is in these margins that bookies make a lot of their money. The odds on a Lancashire victory in a Roses match can be shorter in Manchester than Leeds as there are more punters on the west of the Pennines prepared lay money on a red rose victory, even though the returns are lower than those available elsewhere. Perhaps the internet makes this kind of arbitrage more difficult for the traditional bookmakers, but it must be part of the skill of peer-to-peer betting.

The consequences of this phenomenon can be far more serious than losing your shirt to the bookmaker or predictably skewed predictions from sports pundits. It provides the fuel that feeds disputes: each party believing that they can, and indeed should, get more out of a situation than is objectively likely. Lengthy legal cases and protracted industrial disputes can result, costing participants time and money that a compromise could avert.

So Botham, Pollock, et al are not simply being obtuse or stubborn in fancying their team. They are conforming to a very human trait that makes it difficult to distinguish what we want to happen in the future from what we predict will happen. If you want a pundit’s view of the South Africa v England series that is unsullied by wishful thinking, find someone with nothing invested in the result. Jeremy Coney would be my go-to man.

______

Footnote: see more detailed explanation in Tim Harford’s FT article ‘Wishful Thinking‘.

Short pitch: an over

Just 1.1% of a full day of Test cricket; only 5% of a T20 innings. An over is the second smallest unit in cricket, but for a non-bowling cricketer, obliged by the format of a competition to bowl, it has the potential to be the period of time covering the transition from active playing to determined retirement. It lasts long enough for repeated humiliation that then echoes onwards for years ahead.

“You now,” shouts the skipper. The innings is short; the call inevitable. I trot towards the umpire, hand him my cap, and mark a short run-up, wondering if performing these conventional actions can somehow create an aura of bowling competence that will sustain me through the next six deliveries. That number, six, I put out of my mind. I know it’s a best case scenario. It could, with a mechanical merciless umpire, be infinite if I cannot control how I propel the ball. But even six deliveries, with these batsmen, could yield runs so richly that the game could be put beyond us.

Before any more thoughts can overwhelm me, as if approaching a cold pool for a dip, I step forward and send the first ball on its slow flight towards a violent fate. It’s straight and full. The batsman meets it on the half-volley and drives it swiftly to the left of our fielder (one of only four) at wide long-on. The batsmen run one, and there’s a call for a second. A powerful throw reaches the keeper on one hop, the stumps are broken, we shout, the umpire raises a finger. We cheer and congratulate. A new batsman comes to the wicket, takes guard.

So much has happened. The over should be finished soon, I feel. But, no, it has barely begun – five more balls required.

So, back up to the crease, getting this unpleasant duty done. Another drive sends the ball skimming straight past me to the boundary. The ball is returned to me and I wave the four fielders straighter. I should have done it at the start of the over, but the notion of setting a field for bowling that I feel I can barely control, seemed like tempting fate.

Here we go again, before my hand starts to tremble, a couple of steps and over comes my arm. I’ve managed to keep it full again, but this one is heading for the batsman’s legs. Down comes his bat, but somehow, probably through lack of pace, the ball evades it, hits his pads and bounces a yard or two into the legside. The batsmen run a leg-bye. My team-mates shout encouragement to me. I’ve made it to the half-way mark. It might be comical, these slow looping lobs, but I’ve not yet felt humiliated or put the game beyond us.

The tall opener is now facing me. Forward I go and launch another benign missile, which he steps out towards and drills past my left hand, ball bounding to the straight long-off boundary.

Not far to go now. I let a thought of technique into my mind as I move into my next ball: to pivot on my front foot so my chest rotates from facing leg to off-side. The tall opener clatters my next ball to my right. A full-length dive on the boundary cuts off the ball and keeps the runs down to two. I stop and applaud, relieved to be spared a boundary; embarrassed by the gap in quality separating my bowling and the fielding.

My finishing line, my summit is approaching. I don’t want to ruin things now. That sense of protecting something carries through into my action and, hardly possible one would think, I put even less on this ball, which floats along the 20 yards, descending towards the batsman’s thigh, in front of which he waves his bat and spanks it past the square-leg boundary.

“Over,” calls the umpire and I am released.

Short pitch: the immanent game

For twenty minutes, cricket dominated, absolutely. Second by second, it controlled everything and its imprint was everywhere. Every muscle contraction was dedicated to the game. Each thought a construction of this match and its near conclusion. My psychology awash only with hopes and dreads of what my contribution might be. Relationships with teammates defined solely by our combined need to squeeze a result. Of the opposition, depersonalised antagnoists, on whom failure was all I wished.

The firm turf, felt only for what it meant for a cricket ball: swift passage to the boundary if hit a degree or two away from me. And the light, closing in on the game. The rotation of the planet obscuring the sun, progressively denying us sight of the struck ball until it was upon us or past us in the field. From there, back into my mind and the urgent hopes for victory and fears of shame should I be culpable in our defeat.

Immanence, the property of being everywhere, suffusing all experience, associated with ideas of deity, was the state of this cricket game.

For two hours, the match had hinted at, and never excluded the possibility of a tight finish. Our total strong; but their reply measured, then accelerating, until wickets fell, a batsman was required to retire and the run in, those swamping, absorbing twenty minutes.

Despite the intensity of those last minutes, I can’t recall ball-by-ball how the final over progressed. But with five needed from two balls, nine of us were stationed on the boundary, calculating if a stride either way could be definitive and eyes straining for the ball.

Neither of those deliveries turned out to be the examination of my moral courage and fitness for this sport that my mind had convinced me they would be. A single and a dot finished the game. We shook hands, we celebrated, we joked about heart conditions and eye strain. Cricket receded a little, allowing in physical sensations unfiltered by the game – thirst, muscle ache – and emotions – pleasure for a successful teammate, enjoyment and relief.