Do breaks in play take wickets?

It seems uncontroversial to state that batsmen are more likely to be dismissed immediately after an interval, than when they have settled back into the new session. But similarly well-worn aphorisms – the nervous nineties and batsmen tending to fall quickly after sharing a sizeable partnership – have shown not to stand up to statistical scrutiny. This post, therefore, attempts to apply numerical analysis to the received wisdom that in Test matches batsmen are more vulnerable immediately after resuming play.

Before introducing the numbers, it’s worth reflecting why this common understanding is so readily accepted by cricket followers. I think there are two mutually reinforcing factors at play, each of which could be supported by associated statistical evidence.

The first factor is that batsmen are at their most vulnerable early in an innings. Owen Benton, in his post ‘When is a batsman ‘in’?‘ demonstrated that the likelihood of a Test opening or middle order batsman falling before scoring another five runs is at its highest when on a score below five. It can be argued that this early-innings fallibility revisits the batsman in the analogical position of re-starting an innings after a break in play.

The second factor is that it is accepted good tactical practice for the fielding side to start the session with its most potent bowlers. While there are no statistics to hand to demonstrate that this tactic is actually applied regularly, nor that those bowlers are more threatening immediately after a break, it would be straightforward to compare the career strike rates of the bowlers opening after the resumption against other bowlers used in that innings.

To test the proposition that wickets fall more frequently after a break in play, I selected a random sample of Test matches played since May 2006 (the date from which cricinfo.com scorecards recorded the score at every break in play). Details on the sampling method are provided at the foot of this post.

From the sample of 20 Tests, I noted the incidence of wickets falling in the three overs following (and prior to) 436 breaks in innings, including lunch, tea, drinks breaks, close of play and weather interruptions. Excluded from this figure are any breaks which coincided with the start of a team’s innings.

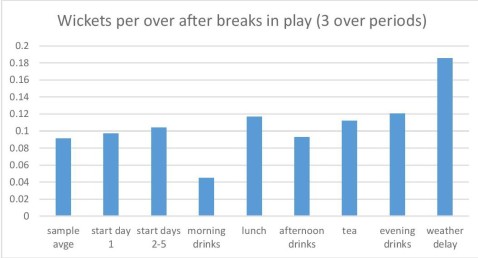

All results are strike rates expressed as wickets per over. In the period 2006-2015, wickets fell on average in Test cricket at 0.08 per over. As the chart below depicts, there was a 50% increase in the strike rate in the first over after a break in play (0.125). This effect wore off rapidly, so that the second over after the resumption saw a strike rate (0.090) that was barely above the period average and equivalent to the sample average (0.091).

The result for the 1st over after a break in play is statistically significant. The sample size doesn’t enable the analysis by type of break in play to be anything other than indicative, but is presented below for interest – based upon the first three overs of the restart.

Weather breaks appear to be the most damaging to a batsman’s prospects, but the 20 Test sample only featured 11 weather breaks. There does not appear to be any relationship to the duration of the break. For example, the overnight break was associated with a lower strike rate than the brief evening drinks break.

The sample results do seem to bear out the received wisdom that batsmen are vulnerable immediately following a break in play. However, the brevity of the impact – a single over – doesn’t strongly support the two explanations offered above.

If batsmen find a new session is like starting a new innings, then the effect would be visible in the second over, as six deliveries is unlikely to be sufficient for both batsmen to pass this phase.

If the phenomenon is caused by the more potent (and refreshed) bowlers, it too would be discernible in the second over (bowled by the other fresh strike bowler) and third overs of the new session.

There remains an explanation and it’s a prosaic one, which will often be used by commentators seeing a batsman fall soon after a break. It may simply be that the batsman’s concentration has been interrupted and not sufficiently refocused for that first over of the restart. There’s a message here for players – prepare psychologically for the new session – and spectators – don’t dither, get back to your seat for the restart.

——————————-

Sampling method:

383 Test matches were played in the period from May 2006. Based on an estimated 9,000 breaks in play with an expected strike rate per 18 deliveries of 0.3, 478 breaks in play were needed to give a result with confidence interval of 0.04 at a 95% confidence level. Excel’s random integer function was used to pick numbers between the Test match references of the first (1802) and last (2181) in the sample period. It is worth noting that the random sample was based on Test matches, not breaks in play.

Using the number of relevant breaks in play from the 20 Test sample, a lower total number of breaks of play in the population was calculated for the population of Tests: 8,600. The adjusted sample size was 417, which is lower than the sample on which data was collected.